For a long time, table tennis has been treated as a light sport. Fast, technical, elegant, and precise, but physically modest when set beside strength or endurance disciplines.

However, the modern game operates under conditions fundamentally different from those that shaped earlier generations. Dense competition calendars, frequent intercontinental travel, ranking-driven pressure, and multi-event participation stack into the sustained load. That produces structural fatigue, a gradual erosion of precision, clarity, and resilience under continuous demand.

Wang Chuqin stands at the center of this reality.

His run through China Smash and WTT Finals made the hidden cost difficult to ignore. He dragged himself from event to event, from match to match, clearly running on empty, both physically and mentally. The performances were widely praised for resilience and willpower, but what lay beneath?

Whether the overload came from team expectations or from Wang’s own drive matters far less than how completely it was normalized. Strain was framed as honor, obscuring deeper structural problems not only within the Chinese system, but across modern table tennis as an industry that has failed to keep pace with its own demands.

1. The Modern Game Outgrew Its Old Assumptions

Over the past two decades, table tennis has undergone a series of structural changes. Equipment updates, rule reforms, and tactical evolution softened extremes of spin and lengthened rallies.1 But the deeper shift came later.

The overhaul of the ITTF ranking system in 2018, followed by the launch of the World Table Tennis (WTT) structure in 2021, reshaped the rhythm of elite competition. The sports business now thrives on a rolling global circuit with minimal interruption. Since mixed doubles was added to the Olympics in 2021, elite participation has expanded across multiple events within the same tournament, often on the same day.

The shift isn’t simply “more matches” but a persistent increase in overall competitive exposure without recovery margin.

1.1 What Table Tennis Actually Demands

From the outside, table tennis still looks light. Internally, it’s anything but.

Physical and Metabolic Profile

Table tennis is an intermittent, high-speed sport built around repeated explosive efforts. A typical rally lasts about 3-5 seconds, followed by 8-10 seconds of intervals, repeated hundreds of times during a match. Energy production during rallies relies primarily on the anaerobic alactic (ATP-PC) system, which supports rapid force production and acceleration. The aerobic system plays a crucial role in recovery between points and rallies, restoring phosphocreatine and stabilizing physiological function.2

Blood lactate levels generally remain relatively low, reflecting limited reliance on sustained glycolytic metabolism.3 This is why the sport is often misread as low-demand, even though the stress is simply distributed differently.

Metabolic load varies by playing style. Offensive players emphasize high power and rapid output, whereas control players engage in longer exchanges that increase neural processing and recovery strain.4 Across styles, match play consists of recurring micro-stress and micro-reset cycles. Quality must be reproduced again and again with limited resets.

Technical and Neuromuscular Execution

Technical execution depends on precise sequencing across the entire kinetic chain. Force begins in the lower body, transfers through the trunk, and is refined through the shoulder, forearm, and wrist. Minor deviations in posture or timing can alter trajectory, spin, and placement.

Footwork requires rapid lateral movement, controlled rotation, and balance under speed. Stabilizing muscles must fire repeatedly, and neuromuscular coordination must translate intent into action without delay. Execution succeeds or fails in real time.

As fatigue accumulates, coordination tends to degrade before strength does. Movements remain forceful, but less economical. Precision becomes harder to reproduce.

Cognitive and Neural Processing

The cognitive demands distinguish table tennis from most other sports. In tennis or badminton, rallies allow longer windows for visual processing and adjustment. Here, players must decode spin, trajectory, speed, and opponent cues, anticipate likely outcomes, and commit to a response within reaction windows measured in a few hundred milliseconds.5

Decision-making is continuous and irreversible. There’s no margin for correction mid-stroke. The nervous system integrates perception, anticipation, and action selection under uncertainty, with errors immediately exposed.

Psychological Regulation

At the same time, mindset stability is non-negotiable and inseparable from execution. Arousal must be regulated, pressure absorbed, and decisions committed to without hesitation. A brief doubt arises regarding timing and coordination.

Unlike physical fatigue, psychological strain often remains invisible and misread as attitude or form. Yet it directly interacts with cognitive and neuromuscular systems, amplifying errors when regulation slips.

1.2 How Modern Formats Multiply Those Demands

The structure of modern competition amplifies these requirements by reshaping frequency, roles, and psychological context.

Calendar Compression and Must-show

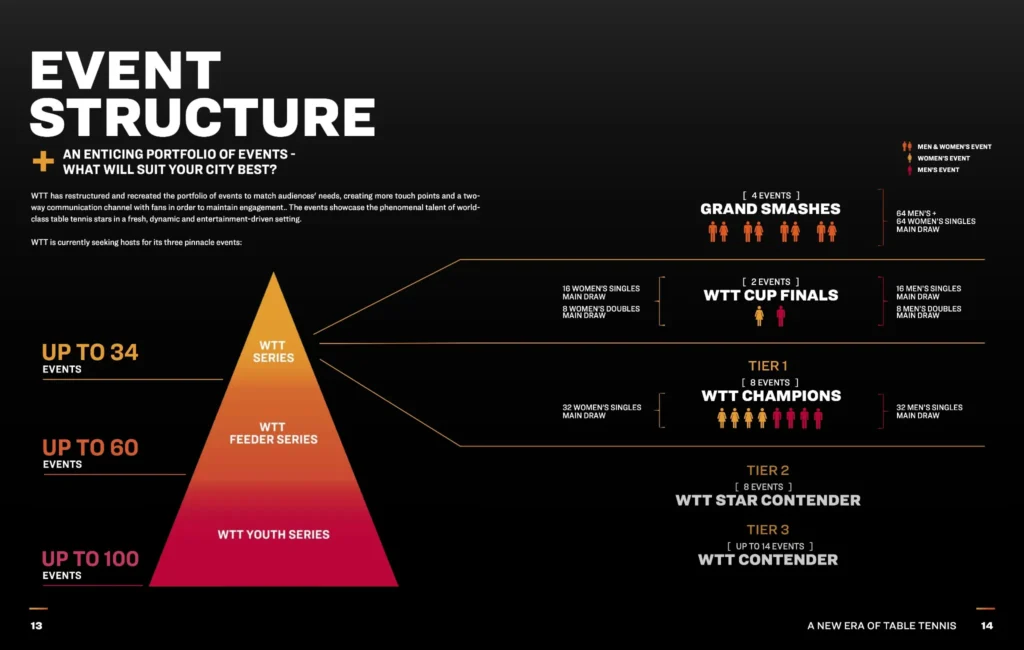

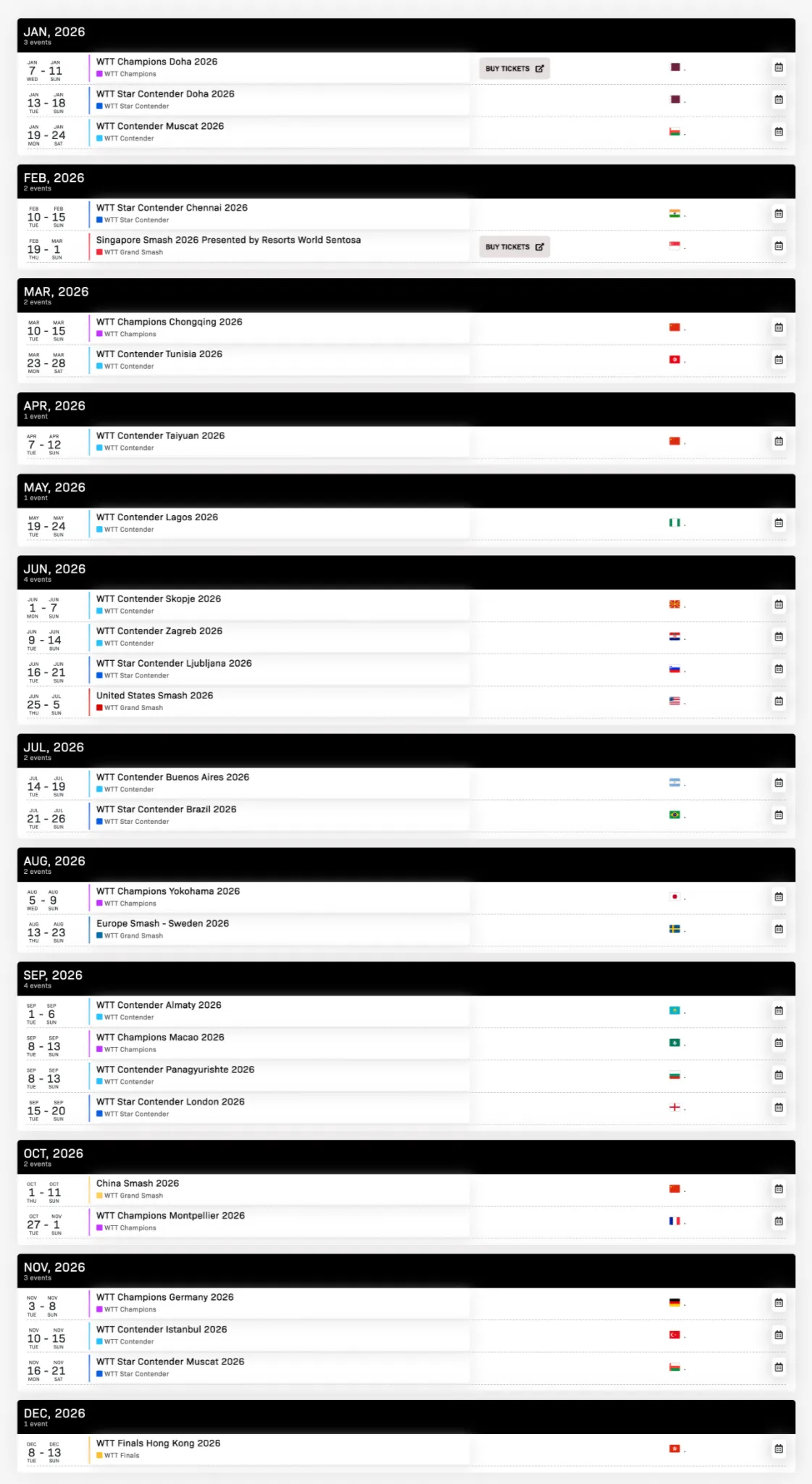

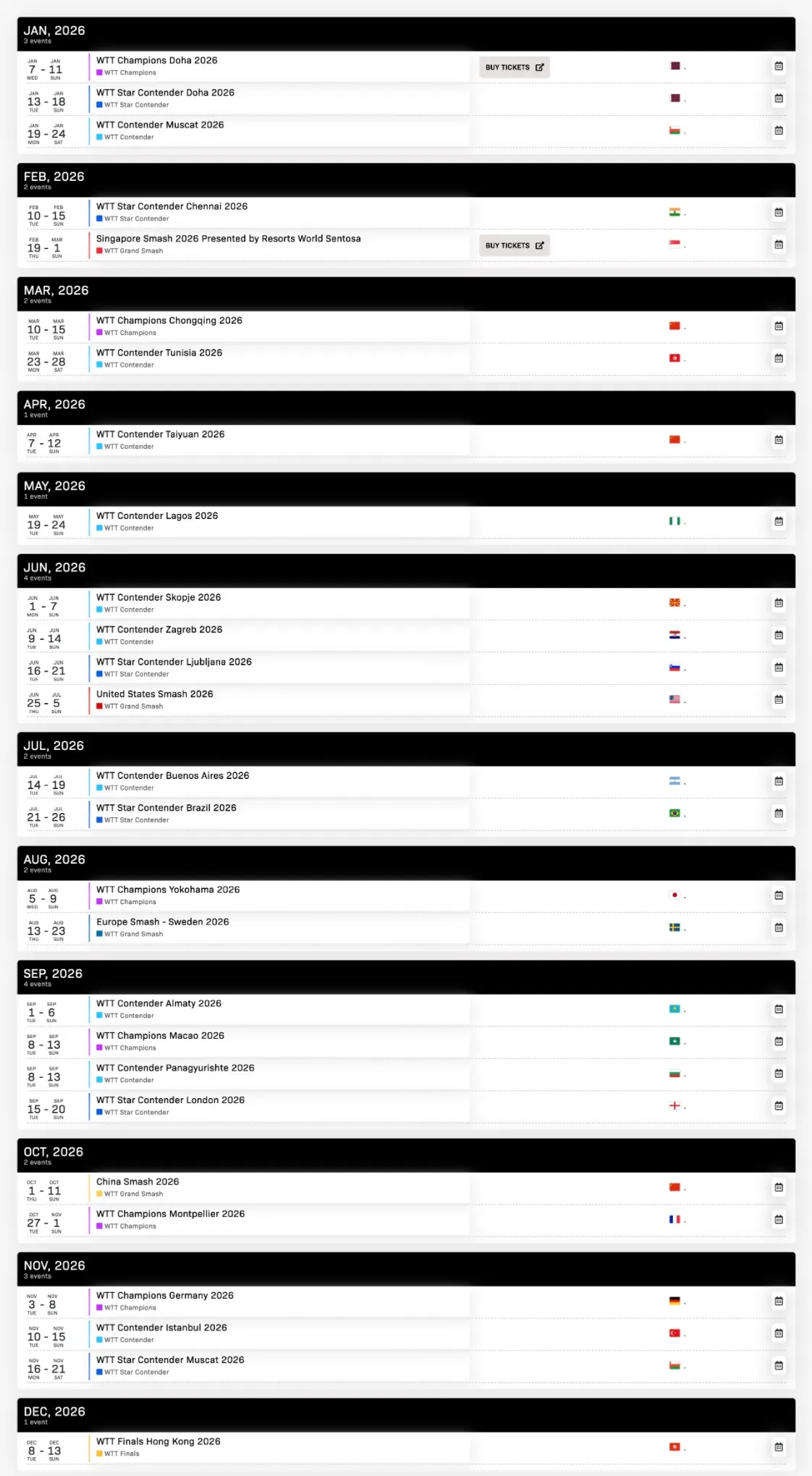

The WTT system functions as a tiered, year-round competitive structure rather than a single-season circuit. Grand Smashes, Finals, Champions, and lower-tier tournaments follow one another across continents with little interruption.6 World Championships, Olympic Games, and continental competitions sit outside this framework but remain decisive for ranking and career progression.

Ranking points are accumulated incrementally across dozens of tournaments. Performance at one tournament directly affects seeding, qualification, Olympic positioning, and long-term career stability, while determining the conditions under which the next is contested.

For top players, participation isn’t fully discretionary. They’re invited and, in practice, expected to enter Champions-level events and above, where ranking rewards are heavily weighted toward deeper rounds. Absence without approved medical or official justification may result in penalties or adverse ranking consequences.7

Former world champion and CNT coach Liu Guozheng has noted that8 in his generation, he competed in far fewer tournaments, often six or seven a year, with sufficient recovery time after each. “Today, major competitions occur nearly every month, sometimes twice within a single month, placing players under fundamentally different and more demanding conditions.”

Multi-Event Participation

Elite players are increasingly entering singles, doubles, and mixed doubles at the same tournament. Each format operates under distinct spatial logic, movement patterns, rhythm control, and tactical responsibility.

Singles requires individual initiative, full-court coverage, and rapid tactical adjustment. Doubles compresses space and shortens decision windows while demanding synchronization with a partner. Mixed doubles brings further asymmetry, altering serve-receive priorities, footwork patterns, power distribution, and rally construction.

The player’s role inside the rally is repeatedly redefined. Timing, positioning, and decision thresholds change. Motor patterns that feel automatic in one format must be suppressed and replaced in another.

For male players, mixed doubles often adds the disproportionate burden. They’re expected to generate more power, cover more space, shoulder attacking responsibility, and finish points under tighter margins. Preparation extends beyond their potential singles opponents to include unfamiliar female opponents and asymmetric tactical dynamics. All of it extra.

Read more

- The Weight Behind the Glory: Wang’s Mixed Doubles Life

- Systemic Bias Against Left-Handers in Chinese Table Tennis

Neural Switching and Psychological Cost

Precision sports depend on stability. Repeated role switching disrupts that stability by forcing the nervous system to reconfigure coordination and timing under pressure. This task-switching increases processing effort and subtly destabilizes fine-motor execution.

Alongside this, modern competition carries few psychologically neutral matches. Ranking anxiety, national duty, public expectations, and commercial exposure shape the mental context of nearly every appearance. Emotional control becomes a part of everyday execution rather than an occasional response.

Taken together, these forces multiply how stress enters the system. Roles fragment, recovery windows narrow, and pressure carries forward from one performance to the next.

2. The Adaptive Circuit and Its Hidden Fragility

Under these conditions, elite performance depends on an adaptive circuit that determines whether stress is converted into adaptation or allowed to accumulate into decline. Our question isn’t whether the load exists, but whether the system can clear it fast enough to preserve precision.

Load and Restoration

Load in elite table tennis is continuous and layered. Competitive exposure, training volume, technical repetition, cognitive demand, and emotional pressure enter the system simultaneously and persist over tightly packed schedules. Each layer builds capacity while leaving residue.

That residue must be cleared. Restoration performs this function.

Restoration works through “fit,” not just time. Neural systems reset through sleep quality and circadian regularity. Energy systems replenish through low-intensity aerobic activity. Movement quality is maintained through mobility work and therapy that address asymmetry and micro-dysfunction. Psychological strain dissipates through decompression that restores attentional control. Medical oversight connects these elements by monitoring readiness and adjusting inputs early.

When restoration keeps pace with load, the adaptive circuit holds, and performance remains consistent. When it doesn’t, residue carries forward across training and competition, quietly destabilizing execution and precision.

When the Circuit Falls Behind

Decline unfolds in a predictable sequence.

Changes first occur at the neural level.9 Reaction speed slows slightly. Perceptual clarity diminishes. Timing drifts by margins that are difficult to detect externally. Decision-making feels compressed even when technical execution appears intact.

With continued accumulation, neuromuscular efficiency declines. Movements demand greater effort to achieve the same outcome. Larger muscle groups compensate. Initial explosiveness weakens. Core-to-limb transfer loses sharpness. Fine-motor control tightens when precision is imposed rather than when it is experienced.

Visible physical fatigue follows. Muscles tighten sooner. Rotational range narrows. Localized issues emerge, then persist. By this stage, however, these signals are commonly treated as routine wear rather than a warning.

Accumulation is the central risk. Each incomplete recovery transfers into the next cycle. Training continues to preserve sharpness. Emotional pressure compounds. Without sufficient decompression, confidence wavers as the body no longer responds predictably. Players already feel disconnected from their own execution.

By the time performance visibly drops, the adaptive circuit has already been compromised for an extended period. What appears sudden is the final expression of accumulated residue. This is why an elite player can move from sharp to flat within days, without a single dramatic failure point.

3. The Adaptive Circuit in CNT Practice

The widening gap between load and restoration reflects a structural mismatch between how modern table tennis now operates and how its leading systems remain organized.

China’s national team is the clearest example. It produced generations of champions through unmatched depth of talent, technical mastery, and discipline, reinforced by a rigid and autocratic internal structure. Yet that once-effective model is no longer sufficient to protect the adaptive edge on which modern performance depends.

3.1 Volume-Based Training Culture

CNT’s training culture continues to emphasize volume and intensity. Long training blocks, heavy technical repetition, and constant competition are treated as basic preparation. Players are expected to absorb high workloads and demonstrate stability under pressure.

Physical preparation focuses on functional strength and movement stability rather than maximal output. Most work, including rotational control, proprioceptive drills, plyometric patterns, and high-intensity interval training (HIIT),10 is performed at moderate intensities around 60-70% of 1RM.11 This allows speed with clean mechanics, and because the intensity looks controlled, the workload is often interpreted as manageable.

Alongside these, multiball drills, footwork patterns, serve-receive routines, reaction training, and pressured timing exercises place continuous demands on execution, perception, and neural processing. Each piece makes sense on its own, but together the strain builds in ways that are harder to detect than muscle fatigue.

In this environment, competition itself becomes part of training.12 Professional matches are used to harden execution, thicken experience, and stabilize performance under pressure. For many players, especially those transitioning from an internally closed training system, competition functions as a necessary extension of preparation rather than a discrete test.

The developmental return of this approach, however, is uneven. For players still building their competitive base, repeated exposure accelerates learning, sharpens decision-making, and strengthens confidence in match conditions. For top players, the effect is different. Early rounds rarely pose sufficient challenge,13 as elite players are often matched against lower-ranked opponents whose primary benefit lies in the experience itself. In these matches, the elite player absorbs most of the physical, neural, and emotional costs while providing a stronger learning stimulus to the opponent, a pattern of asymmetric competitive load.

Only in the later stages of tournaments does competition consistently reach a level that meaningfully stretches the elite player’s capacity. And at the highest level, skill development depends less on repetition and more on disruption. Growth comes from uncertainty, from situations that force recalibration of timing, anticipation, and decision thresholds. When competition becomes predictable, performance stabilizes rather than evolves. Load, however, continues to accumulate. The cost of participation is paid in full even when the adaptive return narrows. Over time, competition shifts from development to maintenance, and then to quiet depletion.

This dynamic is reinforced by the structure of contemporary tournaments. In deep rounds, elite players increasingly face the same opponents again and again. Quarterfinals, semifinals, and finals recycle familiar matchups, compressing variation and reducing tactical novelty. What once carried genuine uncertainty becomes a rehearsed confrontation. Preparation turns increasingly opponent-specific, and competition rewards stability and risk control rather than exploration. Rankings may be reinforced, but the developmental space for top players continues to shrink. Fresh, high-level challenges grow rare precisely when learning is most needed.

Sustained exposure carries another cost. Frequent competition makes elite players increasingly legible. Patterns in serve selection, receive positioning, rally preference, and tactical adjustment become easier to map. Fluctuations in form, physical limitations, and response tendencies are no longer private signals but turn into shared information.14 Over time, this strategic transparency erodes surprise and compresses margins, especially in a field where the same opponents repeatedly meet. What was once a competitive edge becomes a known quantity, not because its quality declined, but because it could no longer be concealed.

Repetition sharpens precision, but also draws on processing capacity. Layered across dense training schedules, frequent competition, travel, and rotating formats, load compounds rather than clears. Because players still appear physically capable, continued output is interpreted as available margin. Reliability entails greater responsibility rather than regulation. What once built resilience now quietly accelerates imbalance in a sport where precision erodes before strength.

3.2 Training Sophistication Without Full Integration

CNT’s limitations don’t come from crude or outdated methods. Training is highly structured, technically refined, and internally consistent. Strength and conditioning prioritize coordination and movement quality. Technical preparation is disciplined and detailed.

What’s missing is full integration. Compared with other elite sports, table tennis still lacks a performance environment that links training load, neural strain, competition exposure, and recovery into a single regulatory framework. Biomechanical analysis, individualized monitoring, neural load tracking, and coordinated medical oversight remain limited.

Training often resembles a table-tennis version of a fancy gym rather than an integrated system that continuously adjusts to the athlete’s internal state. Load is managed through routine and tradition rather than real-time feedback. Solid, but not entirely modern. As a result, early signs of imbalance often pass unnoticed. The system operates as if stability can be assumed until it’s visibly lost.

The sport has modernized its competitions faster than it has modernized its support systems.

3.3 When Restoration Comes Too Late

Restoration practices within CNT tend to be generalized. Cooldowns, stretching, massage, and basic physiotherapy are applied broadly across players, regardless of individual load profiles, event composition, or role rotation. These methods address surface fatigue, not deeper coordination strain.

Support also tends to be reactive rather than preventive. Subtle shifts in coordination feel, reaction sharpness, sleep quality, or subjective readiness rarely trigger adjustment to training or competition exposure. In many high-performance sports, these early signals are treated as actionable data. In table tennis, they’re more often dismissed as ordinary fatigue that should simply be worked through. Adjustment usually follows pain or a visible decline in performance rather than preceding it. Restoration clears symptoms, but it arrives too late to protect the adaptive circuit.

We’ve already seen how this logic plays out over a decade.

Ma Long spent years dealing with knee problems that developed gradually due to long-term wear. Early on, the issue was treated as manageable. Rest, physiotherapy, acupuncture, and local corticosteroid injections reduced symptoms, allowing training and competition to continue. Even as the problem became persistent by 2016 and 2017, intervention remained reactive. At the 2017 World Championships, Ma competed with the aid of the corticosteroid injection15 and won the singles title, reinforcing the belief that management was sufficient as long as performance remained intact.

That logic began to fail in 2018. Pain intensified and started to affect training quality, not just comfort in competition. Swelling lingered, recovery windows narrowed, and confidence in movement grew inconsistent. Conservative treatment escalated from routine physiotherapy to ultrasound-guided injections, repeated joint fluid aspiration, and other emergency pre-match interventions. The priority remained returning to the court, even as the effectiveness of these measures declined. Stability never fully returned. Ma was waking at night from pain, and even basic movement began to feel unpredictable.16

What had long been treated as manageable fatigue revealed itself as a chronic mechanical problem: years of medial collateral ligament stress compounded by calcification at the patellar tendon insertion.17 Injuries of this kind gradually erode load tolerance and function, long before they force withdrawal. As Ma later explained, none of the injuries were severe on their own, but together they formed a complex condition that resisted clear diagnosis for a period of time.18 By the time he disappeared from competition for months,19 the issue was no longer about symptom control but about lost capacity. Such are the limits of symptom-based assessment in prolonged elite competition.

In August 2019, the adjustment finally came. With the CNT’s support, Ma Long underwent surgical intervention in the United States to remove the accumulated issues that conservative treatment could not resolve. He returned to the court shortly thereafter, having rebuilt himself through a demanding rehabilitation period, and eventually regained the top again at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021.

What’s often told as a legend is, in fact, a record of how deep the correction had to go once alignment was finally restored. For years, restoration had reduced pain well enough to sustain performance, but it never reset the system. Success delayed decisive intervention. When the correction finally arrived, it required invasive intervention and a complete step away from the competitive cycle. We can’t fully see the weight of uncertainty Ma Long carried through that period, the self-doubt, the pressure, the noise around him. What we do see is the cost.

3.4 Culture as a Reinforcing Mechanism

Underlying these structural mismatches is a powerful cultural logic.

Within CNT, the willingness to push through fatigue and limitations is considered a primary marker of commitment. Carrying greater responsibility is read as trust. Endurance under strain is praised as character.

This logic discourages early intervention. As long as players continue to perform, internal imbalance is normalized rather than questioned. Precision is trusted to survive volume. Regulation gives way to expectation. Culture here doesn’t create the problem, but prevents the problem from being corrected.

A structure designed to maximize volume struggles to regulate cumulative and rotating load. A system that rarely modulates intensity or event exposure cannot preserve neural freshness. A culture that interprets fatigue as discipline allows neural and cognitive debt to accumulate quietly beneath strong results.

CNT isn’t alone in this. What sets it apart is that its players carry the heaviest load in the world.

4. Wang Chuqin Inside the System

Wang Chuqin’s struggles didn’t begin at the 2025 China Smash. What surfaced there was the visible outcome of a much longer process.

For years, Wang operated at the edge of what a precision-based sport can tolerate. As a core player in the Chinese national team, he’s carried one of the heaviest workloads in the table tennis world. Deep runs across singles, doubles, and mixed doubles became routine. Structural bias against left-handers meant that many technical and tactical adjustments fell on Wang’s own problem-solving rather than targeted coaching and support. Within CNT culture, carrying more simply meant being trusted.

4.1 Prior to the Paris Olympics: No Room to Step Back

In early 2024, Wang appeared in superb form. The fight for a singles ticket to the Paris Olympics forced him into full-intensity competition for ranking points. Other Chinese players secured their positions through system preference and could afford to treat those matches as tune-ups. Wang didn’t have that luxury.

The form he showed during that stretch was later labeled as “peaking too early.” Peak form cannot be held indefinitely. Form rises toward a target event, reaches a peak, and then naturally declines. This is common sense in elite sports, especially within CNT. Under different circumstances, that decline would have been managed through controlled exposure and recovery. But the system’s bias left him no alternative. If he didn’t push fully in the lead-up, he wouldn’t reach Paris. When he did push fully, the later decline was unavoidable.

As the months progressed, travel, crowded schedule, and emotional strain accumulated, pushing his adaptive circuit toward imbalance. Neural clarity dulled first. Neuromuscular tightness followed. Physical discomfort emerged, then persisted. Mysterious injuries appeared in his shoulder and arm in early summer, lingered for more than two months without relief, and followed him into Paris.

Treatment focused on pain management rather than load adjustment. Medical escalation never came. In many modern performance systems, persistent discomfort during dense competition triggers schedule changes, deeper diagnostics, and coordinated oversight. Here, duty outweighed sustainability, and training and competition continued.

After the Paris Olympics, Wang fell into a pronounced slump. And even then, he didn’t have the space to scream for a break. While others received rest windows, he kept competing at the world stage. Walked through losses and confusion, he then rebuilt his form at the end of 2024 through sheer persistence alone. But what followed? If no one else can carry the burden, you must. Reliability brought more burdens.

4.2 China Smash: Winning at the Edge

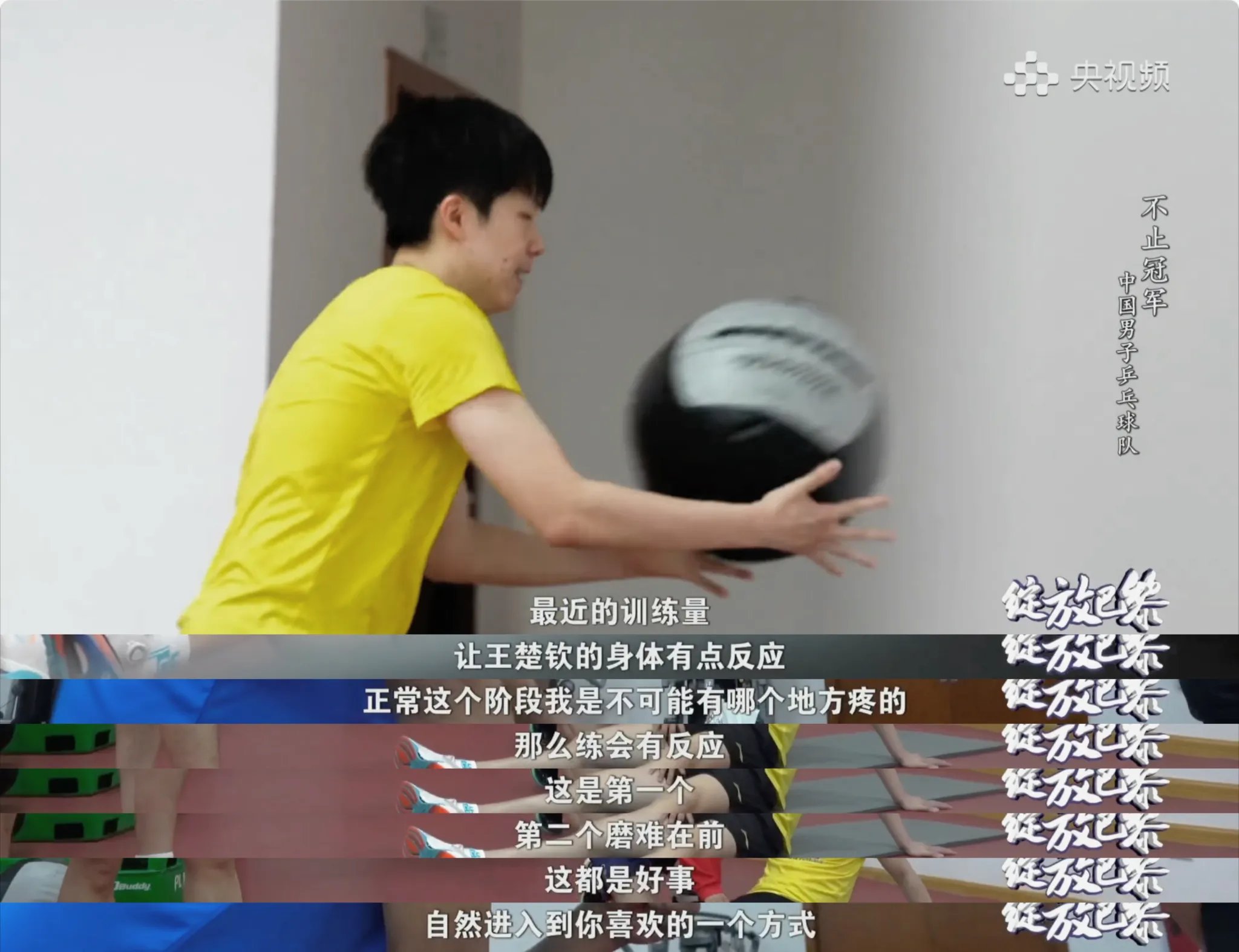

By 2025, the cycle repeated. Wang’s schedule remained among the heaviest in the sport. Early in the year, he spoke openly about balancing training and competition, but that hope never materialized.

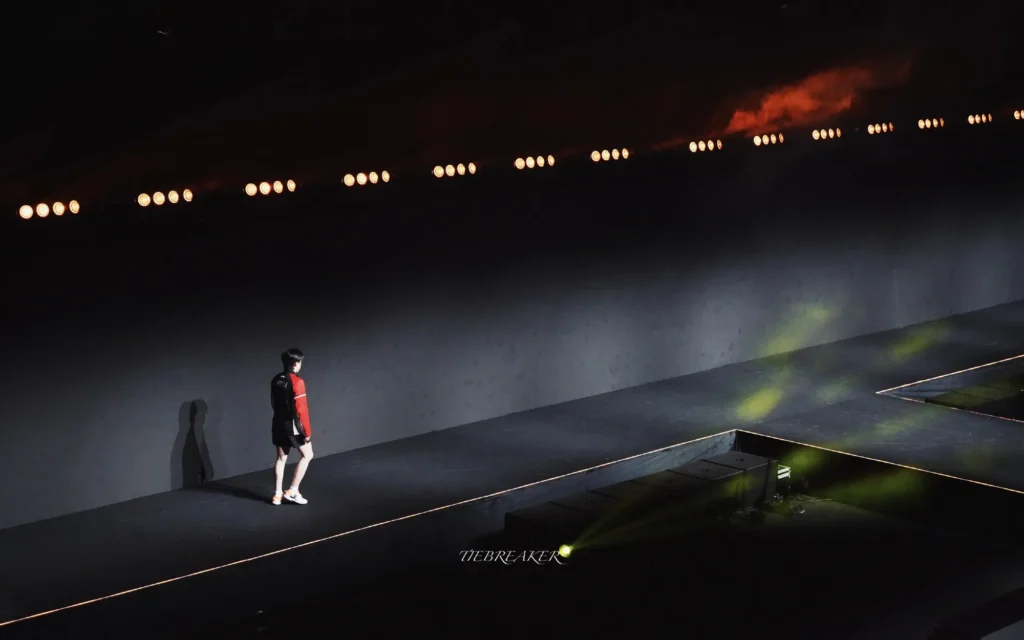

Across seven days of multi-event play at the China Smash, accumulated strain pressed against the limits of Wang’s adaptive circuit. In the men’s singles semifinal against Xiang Peng, signs of physical and emotional collapse were unmistakable. Movement slowed. Swings lost crispness. Breathing grew heavy. Sweat poured as he fought to attack the ball again and again.

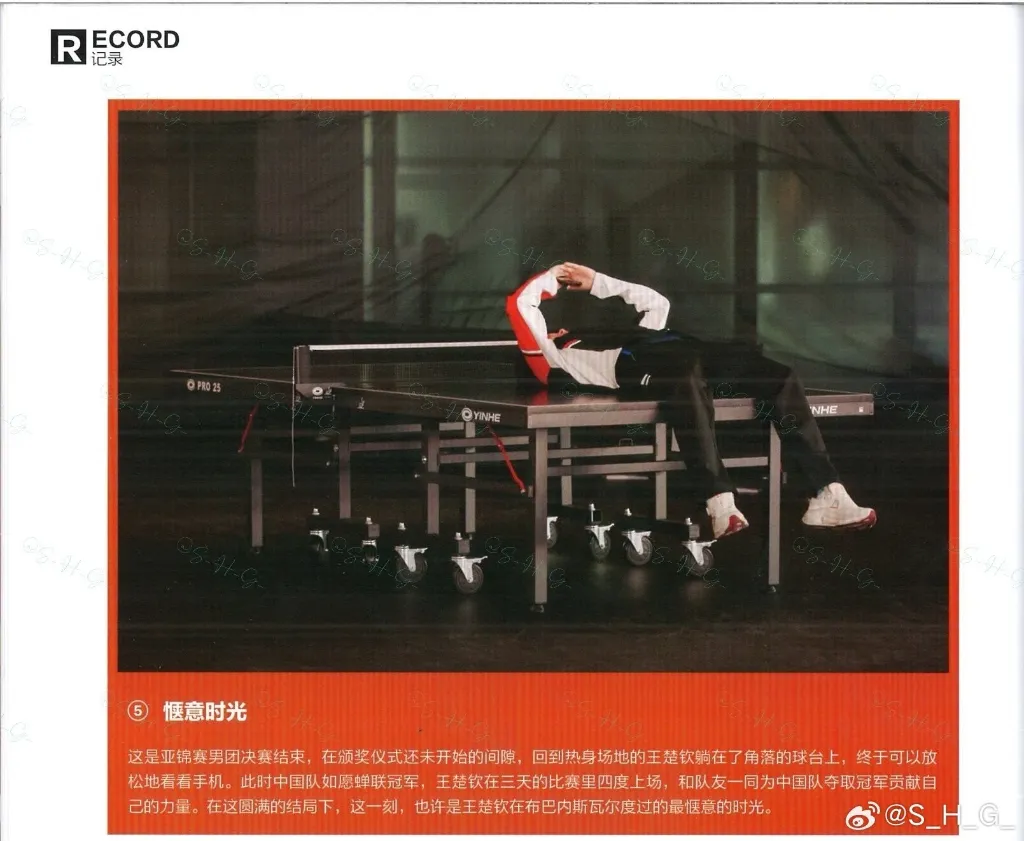

Down 0-2, something in him refused to break. Wang has long believed that until the ball hits the ground, he never gives up. He seized Xiang’s early hesitation in the 3rd game and forced a comeback through sheer will. The crowd responded with admiration. For anyone who understood what was happening, the scene was painful.

Days earlier, he said with a half-smile in an interview, “I’m human, not a robot.” Moments later, he could barely speak.

What appeared heroic was a player overriding safety mechanisms and limits because the surrounding structure offered no alternative.

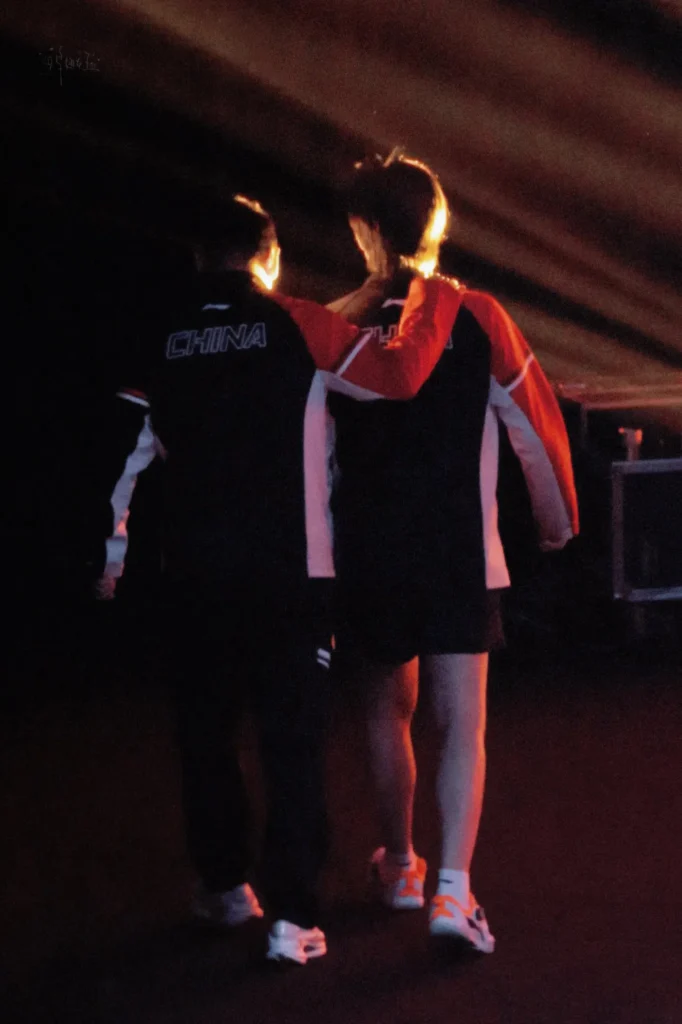

He left China Smash with applause and all three titles. Guess what. Instead of a pause, he went straight into another high-stakes competition at the Asian Championships. Another stretch of demand. Another round of travel and competition. His expressions on court shifted from determined to simply depleted and confused. His post-match interviews sounded flat and distant. Several players clearly drifted during this stretch, including Wang, running behind his own standard.

Liu Guozheng pointed out that what matters most for Wang Chuqin now is how he manages his energy, even though his competitive drive remains strong at the Asian Championships. “His speed has dropped, and his muscle elasticity showed signs of dullness. Continuous multi-event competition brings inevitable fluctuations in form, and he cannot afford to burn himself out.”20

This is the deeper imbalance. When wins appear, strain gets dismissed. When sacrifice yields results, the system interprets it as evidence that nothing needs to change. Authority looks away from the struggles and pain players endure, and the heroic narrative steps in to justify the cost.

Wang moved through a structure that treated sacrifice as virtue, deprivation as discipline, and exhaustion as commitment. Results were celebrated. Mechanisms were ignored. From the Games of China to the Mixed Team World Cup and the WTT Finals and beyond, he was still sprinting on the frontline, with pressure coming from every direction.

4.3 WTT Finals: When “Ordinary” Became Too Much

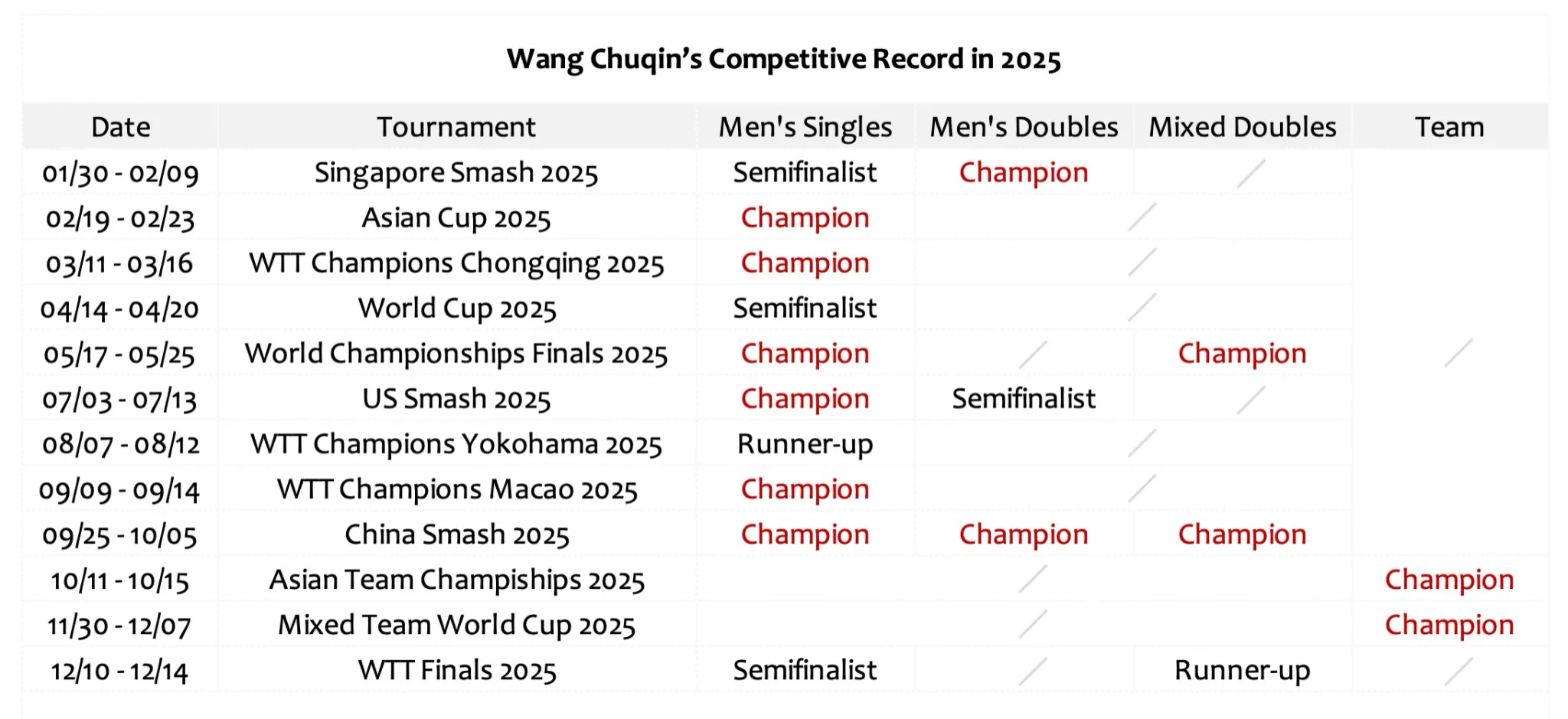

By the time the year-end event arrived, Wang walked into the Finals carrying a weight few players could sustain. In 11 international tournaments in 2025, he had played 120 matches and collected 12 titles across multiple events, including his first men’s singles world championship. China’s domestic competitions weren’t even counted here.

Even for those of us watching, the schedule felt overwhelming. The same matchups recur. Wang against Harimoto. Wang against Moregard. Wang against Togami. Wang against Lebrun. Once or twice a year, these encounters maybe special, but once every month or two? Huh…

By the time the busiest man in table tennis stepped onto the court in Hong Kong, things were already on the edge of collapse.

Besides singles, Wang somehow found himself back in mixed doubles through a host wildcard. This came despite widespread awareness that he wasn’t in stable form due to accumulated load, showed little enthusiasm for mixed doubles, and the host wildcard wasn’t expected to be assigned to the Wang/Sun pairing. Still, he was placed there again. The situation worsened when WTT introduced a nonsense round-robin format for mixed doubles. What had once been three compact matches to a title now required extra group-stage rounds. Combined with best-of-seven formats across the singles draw, the overall load expanded even further.

On the first day of competition, a chaotic schedule left Wang little room to take a breath. His singles R16 began less than three hours after his mixed doubles match. He was seen heading straight to the training hall to prepare for the next match. Asked about the schedule, Wang said simply, “For multi-event players, a packed competition calendar is nothing out of the ordinary.”

Later, he admitted that he had hit a wall and needed time to slow down and reset. “But when I’m representing Team China, I still want to show the right attitude and do everything I can to win.”

Personal resolve, however, couldn’t always overcome physical reality. His strokes lacked stability. Footwork lagged. Timing slipped. Again, only those who understood what was happening knew how painful the scene was. At the mixed doubles final, Wang and Sun Yingsha lost to Lim Jonghoon and Shin Yubin. Surprised but not surprised. Lim later noted that Wang had been playing too many matches recently and was likely worn down.21 That same day, Sun withdrew midway through her singles quarterfinal due to the uncertain injury that had developed over months of nonstop competition.

Then came the final day. Before Wang could step onto the court, he withdrew.

This moment stood out because withdrawal had never been part of Wang’s pattern. We had seen him fight through shoulder pain at the Paris Olympics. We had seen him compete at the 2021 Games of China with an arm that barely lifted. We had seen him gasping for supplemental oxygen in Lanzhou due to altitude sickness. We had seen him struggle through knee and ankle pain, sometimes barely able to stand from exhaustion. He never stopped halfway. Or rather, he was never allowed to.

This time was different. It was suggested that Wang injured his back during morning warm-up,22 severe enough to prevent him from swinging properly. Again, surprised but not surprised. What surprised people was that this seemed to be the first time he withdrew halfway due to a medical issue. What didn’t was that fatigue, stress, and unresolved injuries had been accumulating for months. The warning signs had been everywhere. The long-hanging Sword of Damocles finally fell.

In that moment, withdrawal felt painful, but also clarifying. Pushing through exhaustion and injury should never be treated as something to admire. The real question was whether this marked a shift, whether Wang was finally allowed to prioritize his own protection over team duty, and whether the system was finally prepared to listen.

A day later, the CTTA released a statement announcing plans to strengthen systems for athlete health protection and injury prevention, following the withdrawals of both Wang Chuqin and Sun Yingsha from the Finals. Brief as it was, the statement carried weight. For the first time, the issue was openly acknowledged, linked to real names and real consequences. In the past, even more serious episodes, such as Wang’s injury and racket-damage incident at the Paris Olympics, passed without any official response.

Sounds ironic? The system seemed to recognize the players’ struggles and pain only once they were no longer hidden. But whether that recognition leads to real change is another question. The CNT system failed in 2025. Will it earn trust and respect in 2026? We’ll see.

5. What the System Mistook for Strength

Wang Chuqin’s story is often framed as resilience, responsibility, and toughness, traits deeply admired in Chinese sports culture.

That framing transforms structural failure into personal virtue.

Modern table tennis no longer behaves like the version China once perfected. In the WTT era, the sport operates through dense schedules, rotating formats, and sustained precision demands that leave little room for recovery or recalibration. Systems built on volume, repetition, and the belief that endurance guarantees reliability were never designed to regulate such load.

External structural pressure from WTT intersects with CNT’s internal logic in predictable ways. Participation becomes an obligation rather than a choice. Accumulated strain is treated as something to overcome. Subtle decline is dismissed as a temporary fluctuation. Willpower fills the gap where regulation should exist. Pain management replaces load management. Each win is taken as confirmation that the approach still works.

Within this environment, competition functions as a continuous performance space in which learning, consolidation, and execution are expected to occur simultaneously. Matches feed directly into preparation, and preparation flows straight into matches. Over time, nothing is clearly marked as expendable. Tactical experimentation, developmental intent, and maximal output blur together. Load builds because no appearance is considered disposable.

Simplifying many players’ trajectories, including Wang’s, to heroic narratives misses the point. Damage arrives quietly. Precision dulls before strength fades. Decision-making slows before results drop. When the breakdown finally becomes visible, the debt has already been incurred, and the burden is borne entirely by the player.

In a system that rewards reliability with exposure and treats survival as proof of readiness, similar outcomes are inevitable. Players will continue to carry more because they can, until they cannot.

Unsustainable.

Read Also

Wang Chuqin vs. Systemic Bias Against Left-Handers in Chinese Table Tennis

The Weight Behind the Glory: Wang’s Mixed Doubles Life

Wang’s Olympic Injury Story that We All Missed

Mystery of China’s Coaching System Neglect – Part 2: Wang’s Career with Coaches

Cornered, He Came Alive: Wang’s Stunning WTT Finals Win

References

- Table tennis – Wikipedia ↩︎

- Zagatto et al., Energetic Demand and Physical Conditioning of Table Tennis Players: A Study Review, J Sports Sci. 2018 Apr; 36(7): 724-731. ↩︎

- Kondrič et al., The Physiological Demands of Table Tennis: A Review, Journal of Sports Science and Medicine (2013) 12, 362-370. ↩︎

- Milioni et al., Table tennis playing styles require specific energy systems demands, PLoS One. 2018 Jul 18; 13(7). ↩︎

- Pradas et al., Analysis of Specific Physical Fitness in High-Level Table Tennis Players—Sex Differences, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2022, 19(9), 5119. ↩︎

- Host WTT Event ↩︎

- ITTF Table Tennis World Ranking Regulations, Apr 22, 2025 ↩︎

- Liu Guozheng’s interview, China Sports, Nov, 2025. ↩︎

- Zagatto et al. ↩︎

- Chen et al., Influence of High-Intensity Interval Training on Table Tennis Players, Rev Bras Med Esporte 29 (2023). ↩︎

- Liu Dehua, Effects of Upper Limb Strength Training on Physical Fitness in Table Tennis, Rev Bras Med Esporte 29 (2023). ↩︎

- 适应08年奥运会新赛制 国乒以赛代练不断调整 – 中国乒乓球协会官方网站 ↩︎

- Guadagnoli & Lee, Challenge Point: A Framework for Conceptualizing the Effects of Various Practice Conditions in Motor Learning, Journal of Motor Behavior, Volume 36 (2004). ↩︎

- Davids et al., An Ecological Dynamics Approach to Skill Acquisition: Implications for Development of Talent in Sport, Talent Development and Excellence, 5(1):21-34 (2013). ↩︎

- 一道5厘米的膝盖疤痕,一位重返巅峰的战士马龙_澎湃新闻 ↩︎

- 马龙 | 冠军未退场 时尚先生 ↩︎

- How did Ma Long recover from a knee injury – AISTS Med. Podcast ↩︎

- Table Tennis World, May 2019. ↩︎

- Ma Long injury “more serious than expected” – International Table Tennis Federation ↩︎

- Liu Guozheng’s interview, China Sports, Nov, 2025. ↩︎

- Lim Jonghoon’s interview, Mixed Doubles Final at WTT Finals 2025. ↩︎

- Truls Moregard’s interview, Post-Quarterfinals at WTT Finals 2025. ↩︎

Leave a Reply