For many, Wang Chuqin’s story can’t be told without the shadow and shine of mixed doubles. As a left-hander shaped for the event since his teenage years, it became part of his identity. His partnership with Sun Yingsha grew into one of the defining legends of modern table tennis and opened a new chapter for the sport.

Yet behind all the victories, a quiet conflict lingered. Mixed doubles demand consistency, teamwork, and sacrifice, which built Wang’s success but held him back from chasing his singles dream. Within the Chinese national team, few players bear such divided expectations. His talent made him indispensable, but that same reliability bound him to endless training, overlapping events, and constant adjustment. While others focused on themselves, Wang moved between events, serving the team’s strategy before his own growth.

The story is about the balance between loyalty and ambition, duty and self. In that balance lies both the pride and the pain of left-handers… but not just left-handers.

The crazy sight of Wang once again fighting on (and being trapped in) three fronts at the 2025 China Smash made many pause and reconsider what mixed doubles truly means to him, both then and now. I can’t wait to share my dive and take.

Wang Chuqin and Sun Yingsha claimed Olympic mixed doubles gold and three consecutive World Championships titles, cementing their pairing as a modern table tennis legend.

Disclaimer: I’m not pretending to be neutral or so-called objective. 🤣🤣

Edited on Jan 03, 2026.

1. Wang and Sun’s Chapter of Table Tennis

When Wang Chuqin and Sun Yingsha first joined forces in 2017, few expected they would redefine mixed doubles in table tennis. Eight years later, their record speaks for itself: three World Championship crowns (2021, 2023, 2025), an Olympic gold in 2024, and nearly every WTT mixed-doubles trophy they entered. Their energy on court drew millions of new eyes to the event and began to challenge an old prejudice that doubles would always sit beneath singles.

Behind the legend was a long, demanding road.

When the ITTF announced in 2017 that mixed doubles would debut at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the event suddenly became a global battleground. Although mixed doubles had long been part of the World Championships, its Olympic inclusion gave it a new level of prestige. Every major table tennis association began building pairs from scratch. Under China’s long-standing dominance, this was one of the rare moments when all nations started on roughly equal ground.

Mixed doubles required one male and one female player of exceptional individual skill, with perfect coordination and complementary styles. At first, even China lacked a ready-made combination that could secure control. Japan struck first. Maharu Yoshimura and Kasumi Ishikawa captured the 2017 World Championships title, signaling that China could be beaten.

China responded by using its deep talent pool and echelon-based development system, forming pairs through trials. The first generation centered on Xu Xin and Liu Shiwen, veterans in their late twenties. The second generation, Wang Chuqin and Sun Yingsha, began pairing even earlier in 2017 when both were just 17, trained from the ground up for the future.

Xu and Liu found early success before the pandemic. But at the postponed Tokyo Olympics in 2021, under the world’s brightest lights, Japan’s Jun Mizutani and Mima Ito beat them in the final. For China, that was more than a sporting defeat. To fall in the debut of an Olympic event to Japan, its closest and most complex rival, carried political weight. It felt like a slap on China’s face. Xu and Liu soon stepped off the world stage due to injuries and forms, and Wang and Sun, still young but already hardened, inherited the mission to reclaim dominance.

The weight on them was immense. Outside, Japan and Korea were rising stronger. Inside, the system’s obsession with Olympic redemption burned hotter than ever. It was said that Coach Ma Lin once told the team, in words that stayed with Wang until Paris: “I would trade my life for that gold medal.” For Wang Chuqin and Sun Yingsha, there was no backup plan, no room for failure. Every match, every practice, every trip was part of a recovery effort. What looked like an opportunity was also the start of the toughest road of their careers.

2. System, Bias, and Pain Behind the Rise

In Chinese, the Olympics have always defined the highest stakes. Every Olympic gold is a national and political symbol, a point of pride woven into Chinese cultural identity. Table tennis has been called the “national sport” since the 1950s and become a vessel of unity, identity, and even diplomacy.

Since table tennis entered the Olympics in 1988, each format change has reshaped the hierarchy within the Chinese national team. Yet through every reform, singles remained the crown event, seen as the purest expression of a player’s ultimate ability. All resources, rankings, and reputations orbit around singles performance. Men’s and women’s doubles were removed after 2008 and will return in 2028, while mixed doubles debuted in 2021. These events are valued but secondary, often treated as safeguards for medal counts.

After China lost the first Olympic mixed doubles gold medal to Japan in 2021, the event took on political and emotional weight it had never held before. It was elevated from a side event to a “never again” mission. The authorities saw it as a test of national control, and the entire system reoriented itself to ensure it could never be lost again. For that mission, Wang Chuqin, a rare left-hander with exceptional potential, became the ideal cornerstone.

Left-handers have always occupied a special yet paradoxical place in the CNT. They are tactically irreplaceable, yet often confined to doubles specialists. Wang was no exception. Though he won many youth singles titles and was seen as a future star, as he grew older, he was gradually steered toward doubles. His breakthrough on the senior world stage came through partnered events. At 18, he won his first men’s doubles gold with Ma Long. At 21, he and Sun Yingsha claimed their first mixed doubles world title. Those victories showed him the opportunity to become the doubles anchor within the Olympic lineup. Because of the match-play system at the World Championships and the Olympics, the three-man Olympic team almost always includes a designated doubles specialist. The message was clear: winning mixed doubles was not only a duty but also a path he had to carve out for himself, the path to the Paris Olympics.1

And Wang Chuqin seized that opportunity.

The CNT builds champions through a pattern. First comes the grinding in training, then sustained experiments and pressure tests at WTT (previously Open Tour) tournaments, followed by breakthroughs on the biggest stages. Wang experienced every step. Even after winning a mixed doubles world title with Sun, he was still assigned to rotate partners in 2021 and 2022 with Wang Manyu, Wang Yidi, and Chen Xingtong, and he won titles with all of them. He became the gyroscope at the system’s center, balancing everyone else’s rhythm. Each success deepened the team’s reliance on him. By the time came to formalize the next Olympic pair, his name looked inevitable.

By late 2022, the partnership with Sun Yingsha was settled, but the workload continued to grow. Compared to Sun, who had nearly secured the Olympic position through her Tokyo silver and coaches’ favor, Wang’s road was longer and harder. He still had to fight for a place in the fiercely competitive men’s squad while also carrying the responsibility of the men’s and mixed doubles. Each partnered event demanded different skills, tactics, and training frameworks.

What followed was the survival mode. Day after day, he trained across formats, switching partners, adjusting to new rhythms, and preparing for extra opponents. At tournaments, his name appeared in all brackets. He often moved straight from one table to another, changing partners and match plans within minutes. The line between development and endurance blurred. No other Chinese player carried such a load. Rest was a privilege, not a right.

Inside the team, overwork isn’t a flaw but a badge of honor. In Chinese culture, suffering is viewed as an investment. The system equates discipline with obedience and exhaustion with loyalty. Those who can bear more are expected to bear more. Teammates often called Wang the hardest-working player in the squad. His ability to play multiple events without complaint was praised as professionalism and resilience. Yet every compliment brought one more demand.

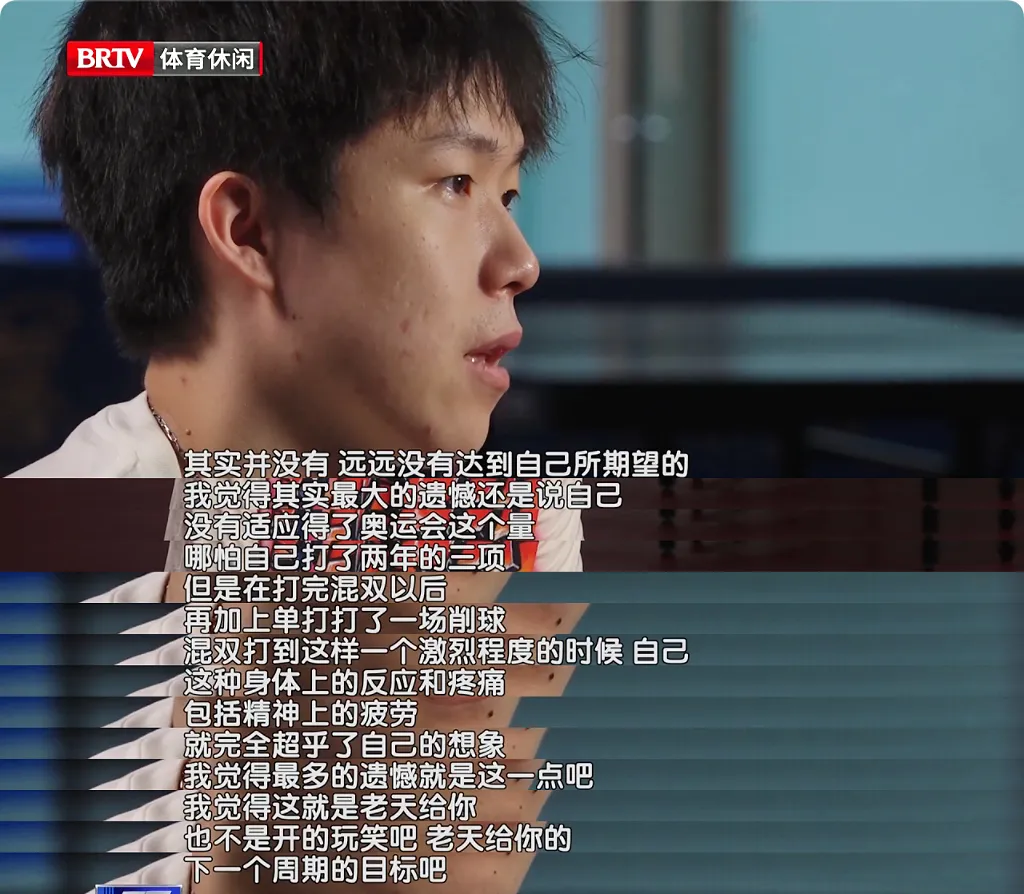

By early 2024, Wang ranked world no.1 in all singles, men’s doubles, and mixed doubles. He had become the team’s indispensable multitasker, but the cost was visible. Fatigue, injury, and quiet frustration began to surface. Constant rotations left little space to refine his own game. His recovery time shortened, his technical growth slowed, and most of his training time was devoted to mixed doubles preparation. He worked harder than anyone, but felt compelled to stand still in the part of his career that mattered most to him. The strain finally erupted at the Paris Olympics.

[Updating: Extended discussion about “Suffering as Investment” in Chinese culture…]

3. Tactical Framework of Mixed Doubles

To understand Wang Chuqin’s conflict, we first need to look at how mixed doubles actually works.

Unlike men’s or women’s doubles, where pairing a left and a right-hander for better coverage is the key, mixed doubles is built on rhythm and sequence. Every rally alternates between the men’s and women’s strokes, so neither hits twice in a row. Each performs distinct yet complementary tasks, shaped by natural differences in power, speed, and physical reach.

At the elite level, the male player acts as the main attacker and finisher. He carries the responsibility for dominating the third ball when his partner serves and the fourth ball when receiving. These are the moments that decide momentum. The female player takes charge of control and transition, using placement and tempo to create openings for her partner. This pattern of “man attacks, woman stabilizes” forms the backbone of modern mixed doubles.

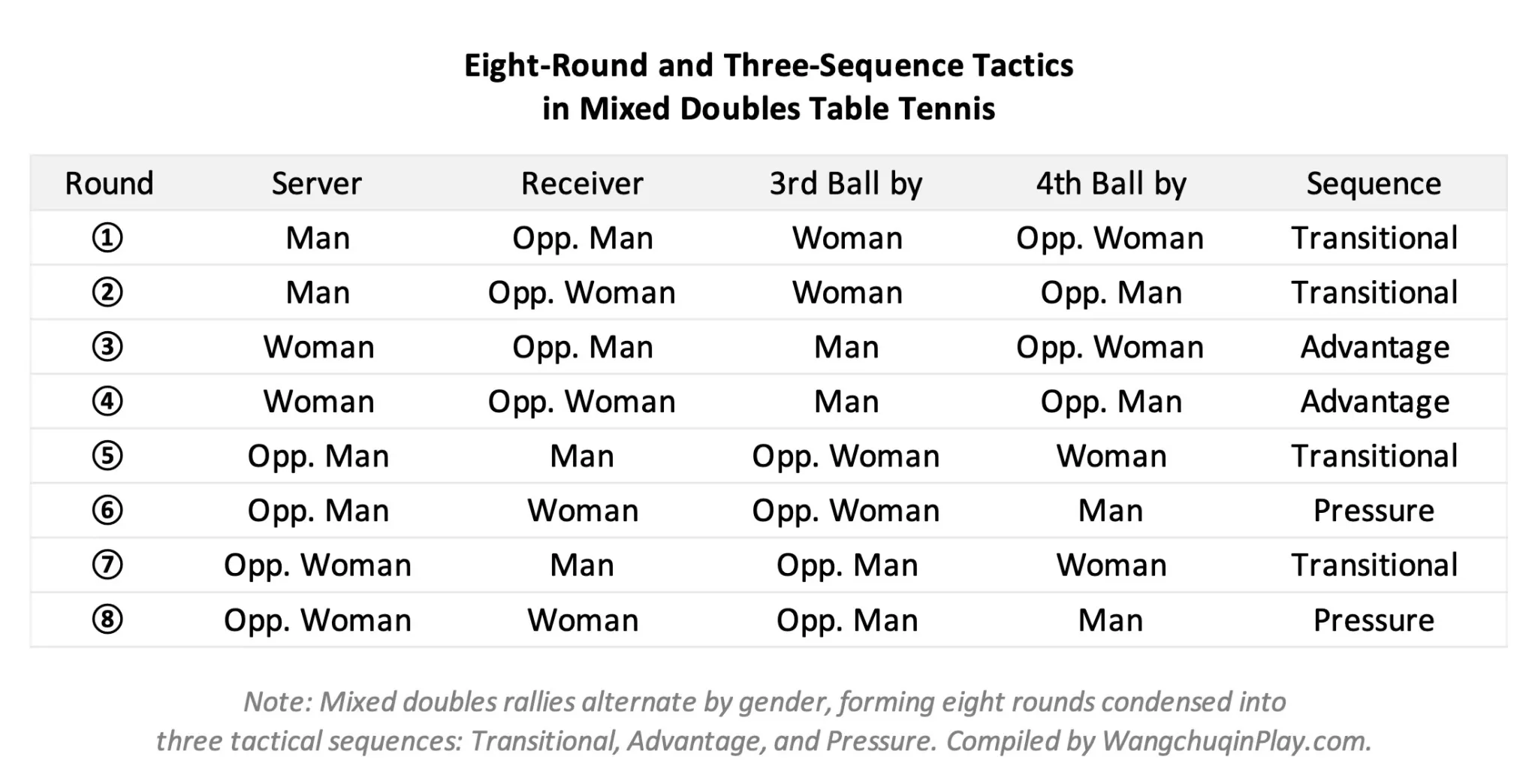

Because of the diagonal serving rule, rallies follow a predictable cycle. In academia, these cycles are often divided into eight rounds, each representing a different gender combination in the serve-return-third-fourth-ball chain.2 These determine initiative and responsibility between partners.

For analytical clarity, these eight rounds can be grouped into three main tactical sequences:3

Advantage Sequence (Serve-Return-Attack)

This is the most favorable scoring phase. It usually appears in Round 3 (F→M’→M→F’) and Round 4 (F→F’→M→M’), where the female player serves with varied spin and placement, and the opponent returns safely to avoid errors, giving the male partner a clear chance to attack the third ball with full power.4 This woman-serve, man-third-ball pattern is the engine of the high-level mixed doubles.

Pressure Sequence (Return-Counter):

This is the toughest phase. In the Round 6 (M′→F→F′→M), the female player must handle a strong serve from the opposing male player. In Round 8 (F′→F→M′→M), the male player must absorb the opposing male player’s heavy third-ball attack. In these rounds, both partners are tested under direct pressure.

Transitional (neutral) Sequences

These are neutral phases without a clear advantage for either side. Some are initiated by the male player (Rounds 1 and 2), others by the opponents (Rounds 5 and 7), and the third- and fourth-ball responsibilities alternate between partners. The points winning depend on serve quality, placement variation, and coordination. A clever serve or return can quickly shift a neutral rally into either the advantage or pressure.

Across all sequences, the male player bears the heavier load as he must convert opportunities and cover for weaknesses. This dual role as both finisher and firefighter creates a quiet imbalance that even the best pairs cannot escape.

4. Wang and Sun’s Partnership

Within this demanding framework, Wang Chuqin and Sun Yingsha have built something extraordinary. They mirror the classic mixed doubles formula, yet their execution takes it to another level. Both stand among the best singles players of their generation, so their consistency, mindset, and game reading naturally blend into the teamwork. The eight-year partnership allows them to sense each other’s rhythm, form, mood, and limits in real time. Few pairs move with that kind of unspoken coordination.5

Sun’s forehand is sharper than most female players, and her consistency is exceptional with very few unforced errors. Wang, known for his explosive third-ball attacks, usually tears open the rallies before opponents can breathe. Their bread and butter is simple but devastating: Sun delivers a precise serve or return, and Wang finishes with a signature loop or step-around smash. Their scoring rate in these advantageous sequences is far above the field.6

They’re just as dangerous in neutral sequences. Wang’s world-class serve often grabs the direct point or easy openings, turning neutral sequences into their second most productive scoring ones. Together, they cover almost every tactical need.

However, no pair is flawless. Sun’s safe returns and limited mid-table coverage sometimes leave open space for opponents, while Wang’s attacking pressure and impatience often drive up his error rate. Still, their complementary strengths more than offset these flaws.

Compared with Japanese and Korean pairs who rely on speed but lack stability, or European duos who rely on variety but lack early control, Wang and Sun stand above the rest. Their mix of explosive power and reliability has made them the textbook pair of modern mixed doubles.

The point is that textbooks don’t account for what happens to the one holding the weight.

5. Wang Chuqin’s Compound Burden

5.1 The Structural Weight

In mixed doubles, the man is expected to be both the firepower and the safety net. For Wang, that means striking early, covering wide, and cleaning up whatever slips through.

When the game stays in the advantage sequences, this pair’s killing weapon, everything flows. As long as Sun delivers an average serve, Wang comfortably finishes the point with a sharp third-ball attack before the rally truly begins.

But once rallies slip into pressure sequences, the load falls on Wang. When Sun chooses a safe or high-arc return to avoid errors, it gives the opponent a clear opening to target Wang. Suddenly, Wang is alone at the table, absorbing a blast or scrambling for a counter.

In those moments, Wang faces a cruel choice. If he blocks it as safely as a regular transition too, the pressure shifts back to Sun, who is among the best in the women’s game but stands little chance against any top male players. Alternatively, if Wang chooses to attack boldly, he runs a high risk of crashing.

Almost always, he chooses to take the risk by executing a high-speed loop or step-around smash with all-in. That said, take the initiative to bear all pressure.

Those dynamics leave Wang carrying both tactical and emotional weight. He’s the engine when things go well and the firefighter when they don’t. The mental demand is far heavier than in singles. What looks reckless to outsiders but is actually responsibility disguised as aggression. As he once said, “As a man, I should take the lead and responsibility. Every shot needs as much quality as I can give so my partner can better handle the returns.”7

Wang’s instinct to protect, to shoulder, and to overextend keeps the pair dominant, but it also wears him down. Every bold swing hides fatigue, and every mistake carries guilt. Fatigue doesn’t respect effort; it slowly erodes focus, precision, and rhythm. What seems like overconfidence is often the weight of the male role in mixed doubles catching up to him.

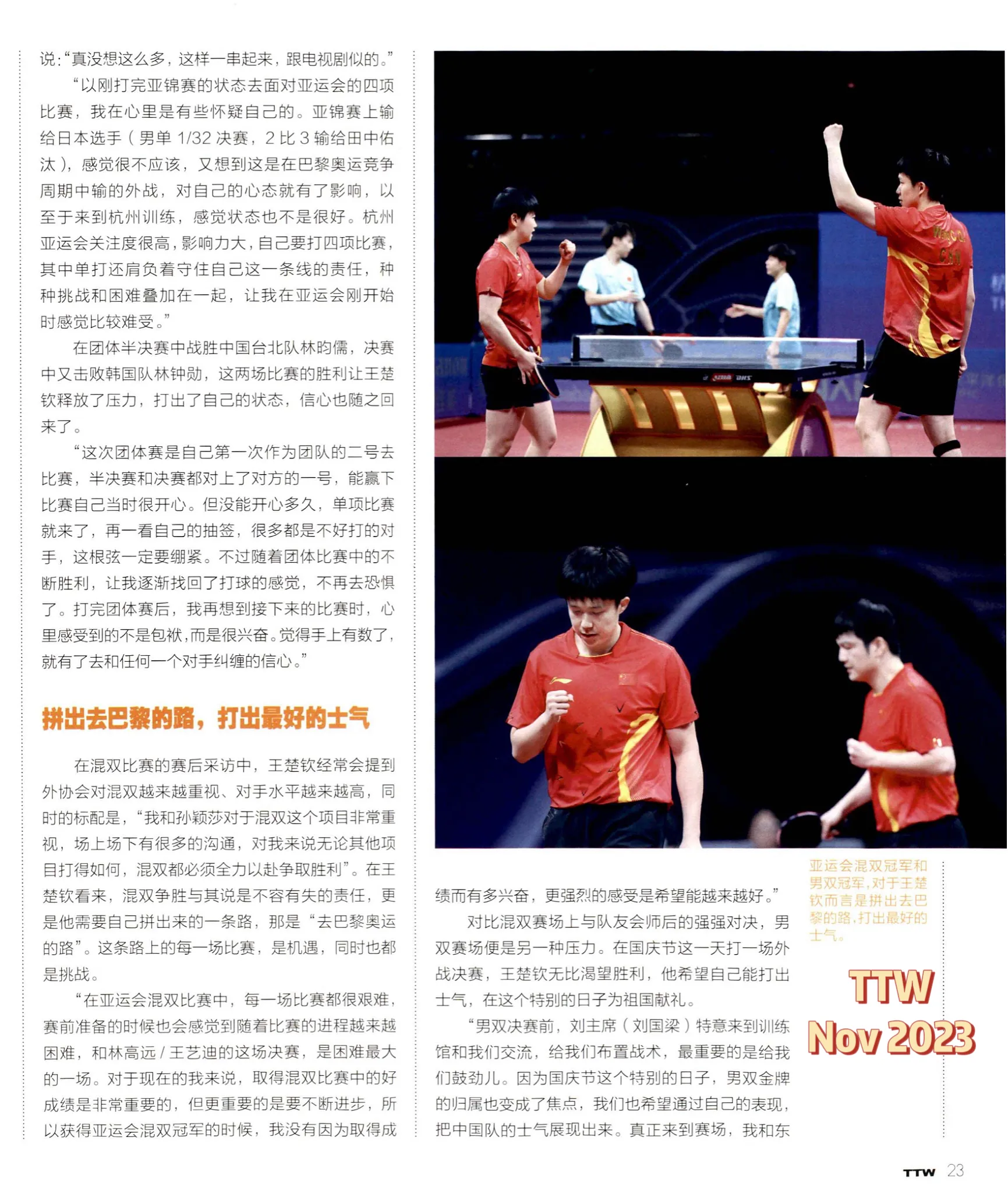

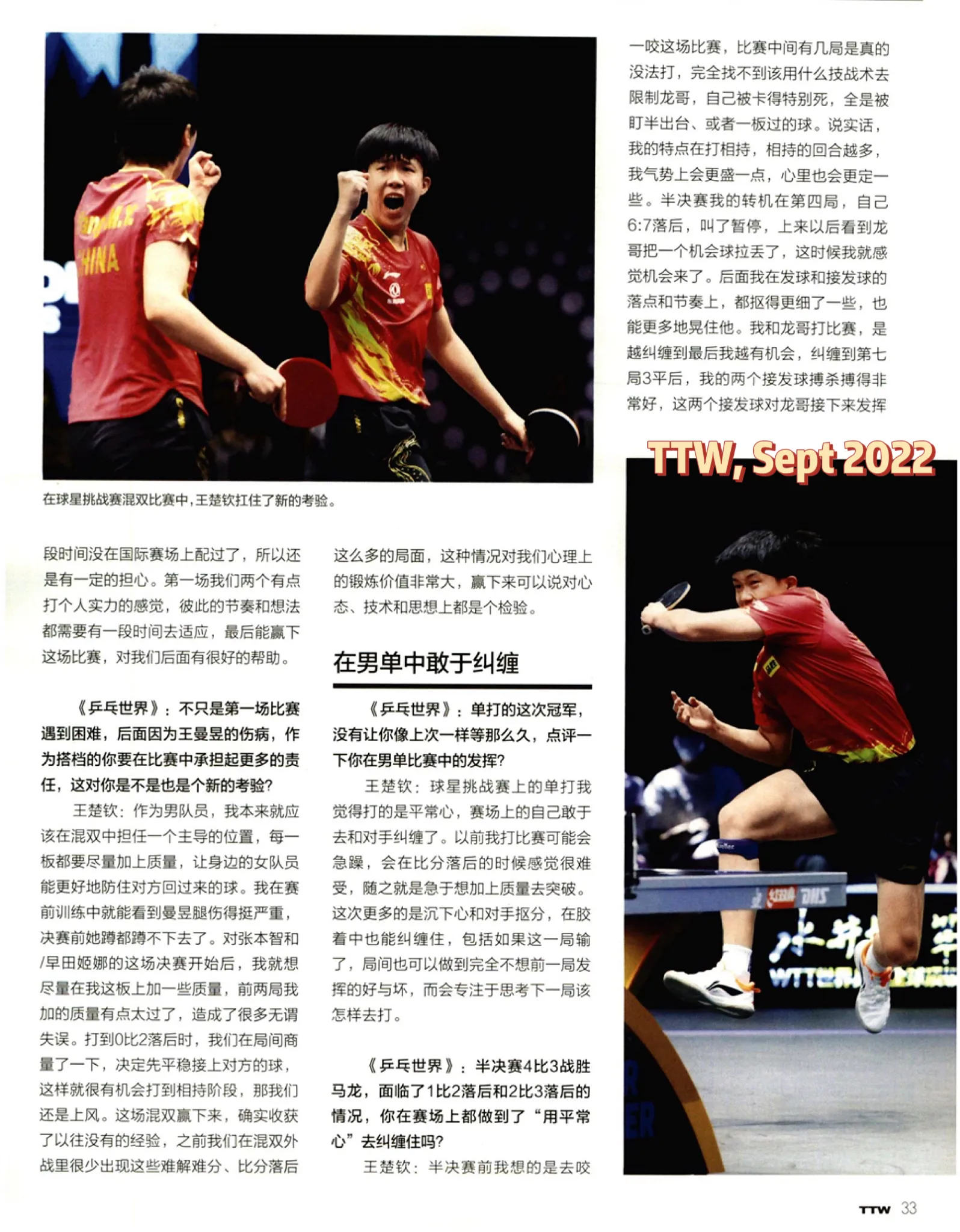

Wang Chuqin said, “As a male player, I should take the lead and responsibility. Every shot needs as much quality as I can give so my partner can better handle the returns. When I saw that Manyu’s leg injury was quite serious, I wanted to add more power and spin to my shots.” Table Tennis World, Sept 2022

5.2 The Partnership Tax

Wang once praised Sun for “raising the ceiling” of their pair. Her calm steadies him, her precision builds rhythm, and her focus helps them recover from chaos. However, her tendencies often make her an easy target for top opponents, forcing Wang to work harder to compensate.

Sun’s stable style has gradually become predictable over the years, and her return habit, often high in trajectory and limited in variation, has turned into the pair’s most targeted weakness. During the 2025 World Championships, Jun Mizutani remarked in commentary that Sun’s returns were rarely threatening, though Japan still had to watch out for Wang’s. Maharu Yoshimura, beaten by the pair in the final, noted that Sun “just returned” Satsuki Odo’s serves, which would have been easy points if not for Wang’s waiting fourth-ball attacks.

These habits are likely by-products of Sun’s singles training, which prioritizes stability and placement over high-intensity counterplay. In women’s matches, a slightly high or passive return, or a less powerful shot, is rarely punished the way it is in mixed doubles. She doesn’t even need to bother correcting her return issue or building counter strength. Additionally, Sun sometimes shows lapses in energy and focus, with slower footwork and reduced movement, especially in lower-tier tournaments.

In those moments, Wang becomes both shield and sword. Besides carrying all the pressure and responsibilities to attack at a higher risk, Wang has covered more mysterious errors that disrupted rhyme, and steps wider, swings earlier, and covers more space. Every safe choice from her demands an unsafe one from him.

Wang never complains. That’s his code. But what looks like harmony from the outside is often him running on empty. When he’s in form, victories seem taken for granted. When he’s off, every error becomes his fault. Critics call him the weak link, saying Sun always carries the game alone, while few remember how much he carries for the partnership.

The noise hit hardest after the Paris Olympics. Wang admitted later he hadn’t performed as expected, even though they won gold. He thanked Sun for leading the matches and encouraging him through fatigue. Yet few recalled the reality behind it… the built-in imbalance of mixed doubles, the years of physical and mental drain from triple-duty, the long-hidden injuries from endless training, especially the extra mixed doubles load imposed by coach Xiao Zhan, whose focus was only on mixed doubles results and whose quiet neglect left those injuries unresolved. (How many “mixed doubles” do I mention here?)

It’s structure, not character. A partnership built on one player’s calm and another’s fire, a system that rewards steadiness and punishes courage. The world praises their balance, but the cost remains uneven.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not interested in casting any shadow on Sun. Some of her limits are simply natural as a woman, and others come from her habits in women’s singles. She carries her own burdens in mixed doubles, though that’s not the focus here.

5.3 Different Impacts on Men and Women

Many say doubles improve overall ability. For women, that’s often true. For men, especially at the elite level, it’s more complicated. At the top tier, the men’s game operates at a way higher level in both technical and physical demands, faster, stronger, and more intense in every aspect.

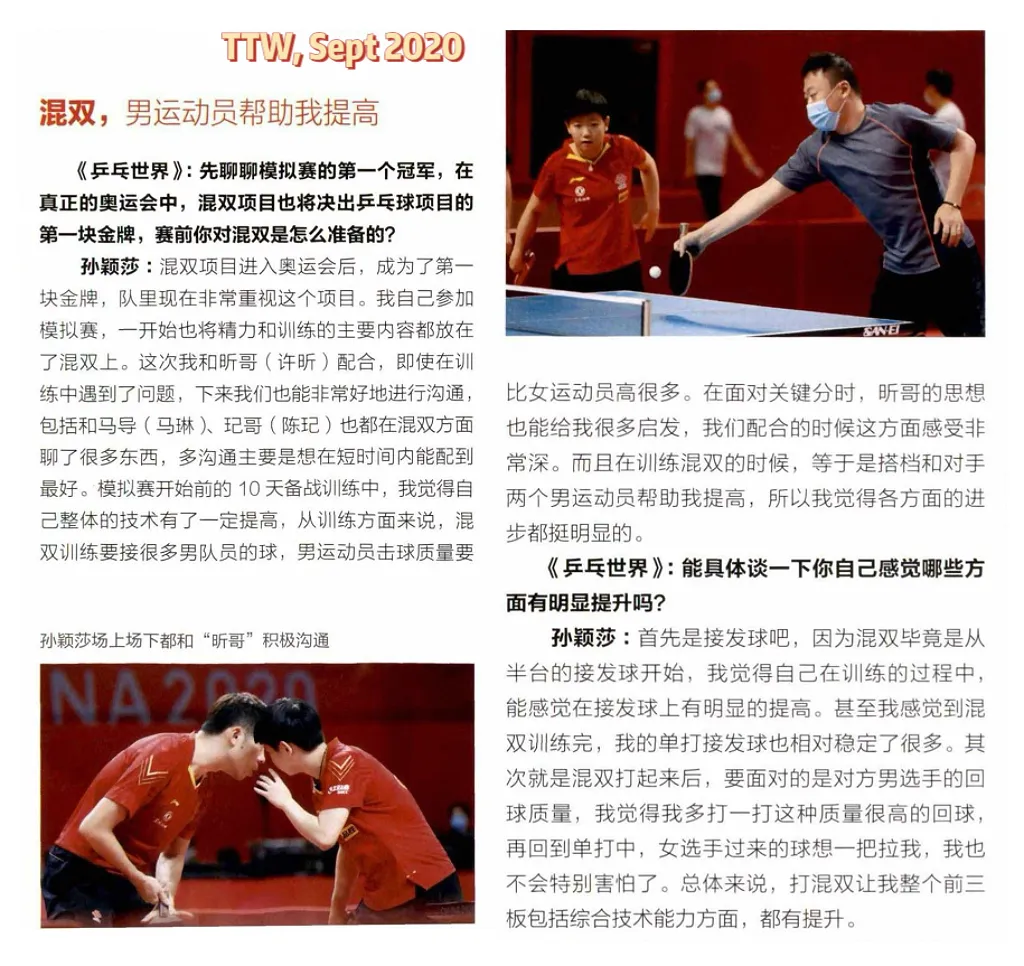

In mixed doubles, female players often benefit from training and competing alongside male partners and facing stronger shots from male opponents. This exposure sharpens their strength, reaction, game reading, and other skills. Sun Yingsha once shared that training and competing with male players improved every part of her game. Her return of serve became more stable, and she grew more confident in handling aggressive returns and third-ball attacks in women’s singles because of that mixed doubles experience. Coach Ma Lin, who once supervised mixed doubles during the Tokyo Olympic cycle, commented that mixed doubles only benefit the woman.

For male players, the story is different. They often face slower rallies and lower-quality shots from female opponents, which do little to challenge their technical or physical limits. Former CNT head coach Qin Zhijian put it more bluntly, saying many male players refused to train with women because they felt the lower intensity and quality were a waste of time.

On top of that, men have to study and adjust to the distinct styles often seen in women’s play. Many female players utilize specialized rubbers or techniques, such as short pimples like Mima Ito, long pips on the backhand like Kim Kum-Yon, or defensive chopping styles like Honoka Hashimoto. These are effective in women’s matches but hold little relevance in the faster, power-driven men’s game.

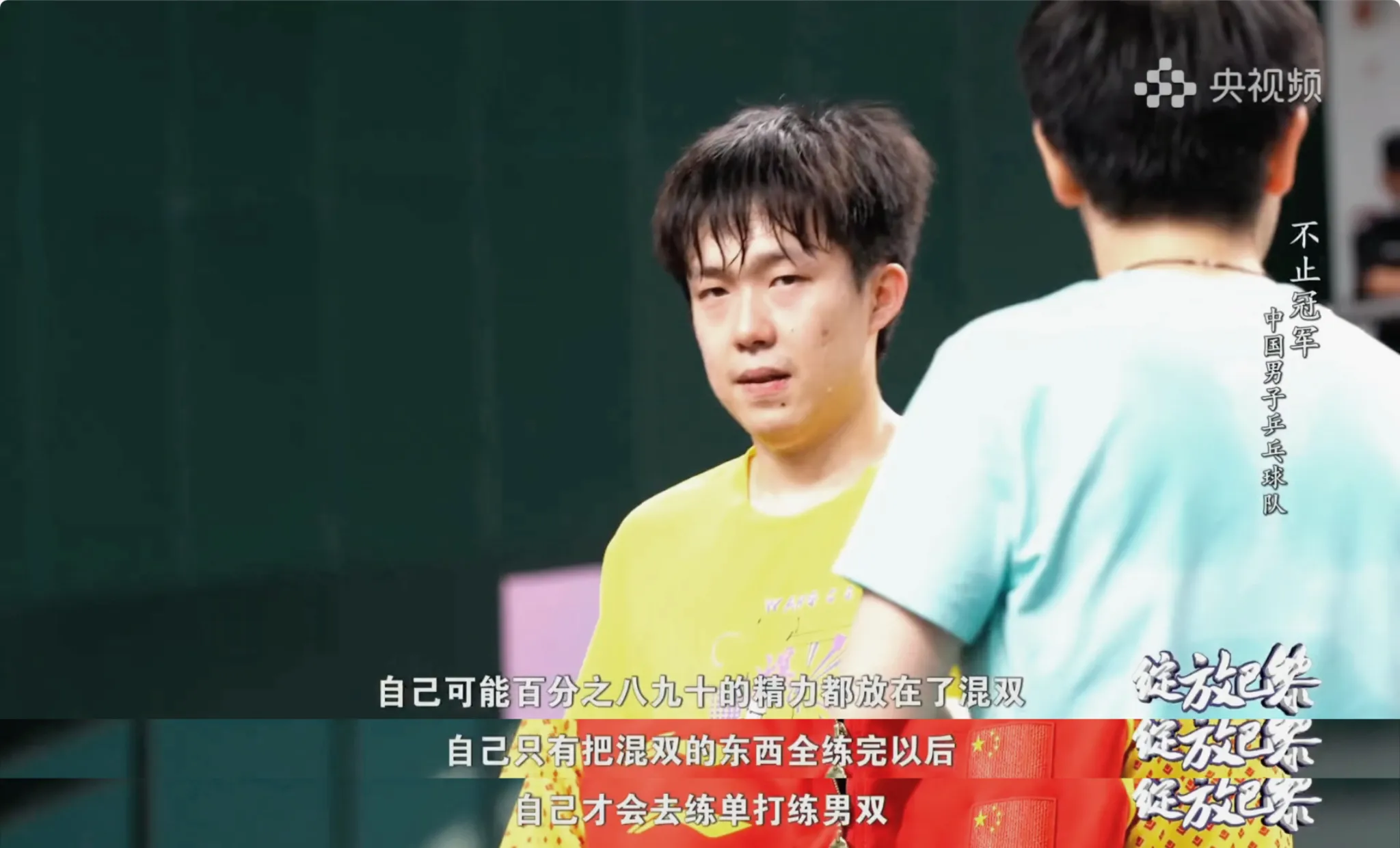

Male players spend significant time analyzing and preparing for these differences. Wang has admitted to devoting most of his training hours to mixed doubles. It often feels like a detour, a loss of valuable training focus, and a process that benefits their partners and teamwork but chained his own progress.

That’s why I keep calling that sacrifice.

5.4 The Hidden Cost of Doubles Thinking

Ten years of men’s and mixed doubles leave deeper scars than most realize. Alternating turns between partners engrains an attack-then-pass rhythm, a natural expectation that the partner will cover the next ball. In singles, that instinct can backfire. Like a step-around smash that feels safe in doubles, with a partner ready to cover the open space, becomes a dangerous opening in singles that an opponent will punish.

Footwork, spacing, and shot choices differ sharply across events, demanding constant mental and movement rewiring. That’s harder than it looks. Returning to singles feels like unlearning muscle memory. Some Chinese male players have joked that a few days of mixed doubles make them forget how to play singles. In fact, nearly all CNT right-handed male players have resisted mixed doubles training for that reason.

Of course, mixed doubles can still offer certain benefits. Players learn to read four-player dynamics, expand their placement awareness, and gain finer control over space and rhythm. Yet for most men, the drawbacks outweigh those gains.

The longer a player stays in doubles, the deeper those instincts sink. The cost is either grinding yourself endlessly and “rewiring” to compensate, or hesitating mid-shot, slowing down in the heat of play, and losing for reasons that make no sense even to you.

5.5 Extra Burdens

Back to the chaos of nonstop training and competitions. In the Chinese national team, it’s common for players to carry both singles and men’s doubles, but adding mixed doubles at the highest level is rare. That means competing from the first round to the final in every event, every tournament. Every day becomes a clash of different tactics, partners, and practicing systems. The physical and emotional strain compounds, but beyond the exhaustion, the mental suffering under the CNT system and the mindset swing between events is even more painful.

During those back-to-back matches with no rest, it was clear Wang sometimes lost patience in long rallies, eager to reset into another third-ball attack phase, his comfort zone and signature style. People often notice Wang’s powerful step-around forehand, admiring its sharpness while also criticizing him for taking unnecessary risks just to look cool. However, it’s obviously connected to his long-term habit in mixed doubles, where he is expected to kill the game as quickly as possible. More importantly, practically, he needs every second of rest he can steal before running to another court. They’re more like a survival instinct. And most of us just simply ignored it.

The system around him adds another layer of strain. Within the national team, Wang still trains primarily under coach Xiao Zhan, who focuses mainly on mixed doubles and views Wang as a medal collector rather than a developing singles player. Without a coach dedicated to his own growth, Wang cannot plan training around recovery or personal improvement. In a system that glorifies exhaustion as a sign of loyalty, balance is hardly attainable. His problem is not mixed doubles itself, but being forced to carry every front without real support.

The extra impacts center on his mixed doubles role: harsh training, neglect of injuries and rest, and psychological manipulation like “sacrifice everything for mixed doubles.” Both a demand and a cage.

6. Future

Even now, as the leading core player and the backbone of Chinese men’s table tennis, and the only player holding various World Championships titles and Olympic golds across multiple events, Wang is still expected to carry all three. Nothing has changed, as if endurance itself were proof of greatness.

At the latest 2025 China Smash, the strain was hard to miss. Wang moved from match to match across three events again, visibly struggling and drained. Energy thinning, smiles forced. In one interview, he said with a half-smile, “I’m human, not a robot.” Moments later, he could barely speak.

Two months later, after a relentless run of competitions, Wang arrived at the WTT Finals already stretched to the edge. And still, Wang and Sun were placed on the frontline of mixed doubles through a host wildcard few expected to go to them. WTT’s new round-robin format only amplified the load. Even Wang admitted that he had hit a wall and needed time to slow down and reset.

Surprised but not surprised. Wang and Sun lost the mixed doubles final, then both withdrew from singles with emergency injuries born of accumulated load. Wang had pushed through pain countless times before. This time, the layers of responsibility, compressed scheduling, and physical and mental fatigue finally closed in, leaving no room to continue.

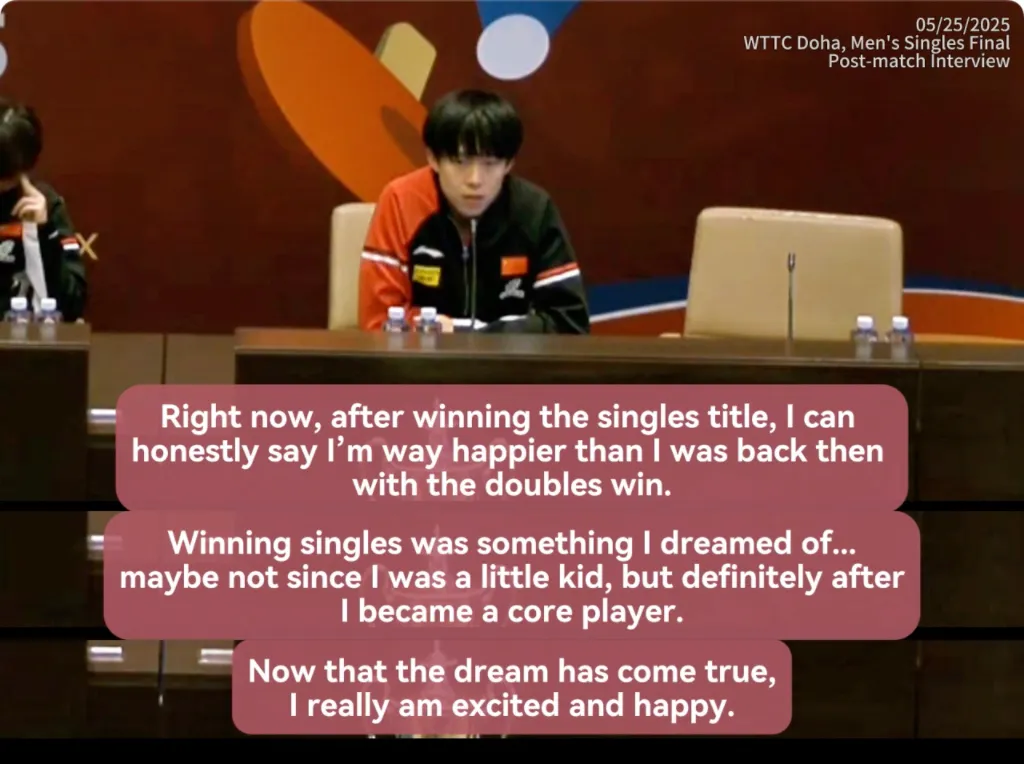

We once believed his situation would change after the Paris Olympics, when his racket broke, his injury was ignored, and he lost his singles match because he was completely drained, both physically and mentally. All of it stemmed from the team’s neglect. I thought they might feel regret, reflect on what went wrong, and correct their mistakes. But they didn’t. Then we hoped his singles title at the WTTC would finally give him a supervising coach, tailored training, and some right to get breath. It wouldn’t. Instead, he was dragged to the worse situation. No one is as capable as you, so you have to carry more.

That line says everything about the system and about Wang’s story. He isn’t just fighting opponents across the table. He’s fighting the weight of a machine that won’t stop asking more from him.

And the hardest part is that he seems have no right to say no.

Read More

Wang vs. Systemic Bias Against Left-Handers in Chinese Table Tennis

Structural Fatigue. Unsustainable.

Mystery of China’s Coaching System Neglect — Part 1: Hierarchy, National Interest, Bias

Mystery of China’s Coaching System Neglect – Part 2: Wang’s Career with Coaches

Wang Chuqin’s Olympic Injury Story that We All Missed

References

- Table Tennis World, Nov 2023 ↩︎

- Zhong et al. 基于八轮次三段法的优秀混双组合王楚钦/孙颖莎技战术分析, 北京体育大学竞技体育学院, 2024. (in Chinese) ↩︎

- Yecheng C. New Exploration of Winning Patterns in Table Tennis Mixed Doubles: Gender Difference Analysis Based on “Eight-Round” Scoring, Journal of Shandong Sport University, 2025,41(3):117-126. ↩︎

- Zhou et al. Is he or she the main player in table tennis mixed doubles? BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 3 (2023). ↩︎

- Jingrui Z. Study on the technical and tactical characteristics of Chinese excellent table tennis mixed doubles pair Wang Chuqin/Sun Yingsha, Master’s thesis, Chengdu Sport University, 2024. (in Chinese) ↩︎

- Xiao et al. The Development of a Table Tennis Outstanding Program of International Competition for Mixed Doubles. International Journal of Sociologies and Anthropologies Science Reviews, May-June 2024. ↩︎

- Table Tennis World, Sept 2022 ↩︎

Leave a Reply