Ever since the Hawk-Eye-based Table Tennis Review (TTR) system arrived at the 2025 World Cup and World Championships, officiating in table tennis has taken a big step forward. Technology is playing a direct role in making calls and has changed how the game feels and flows in a big way.

Watching matches now is just smoother, with fewer nonsense distractions. That endless back-and-forth from online couch critics, grabbing blurry screenshots to defend or attack whoever they like or dislike, no longer holds up. Wang Chuqin, in particular, has endured years of harsh and often unfair heat over his serve. I’ve talked before about why screenshots aren’t solid evidence in these debates, but now with TTR in place, we can finally assess how this system has actually worked so far.

1. TTR System Basics

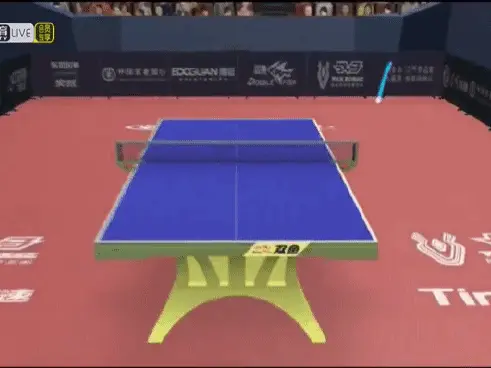

The TTR system is thought to operate similarly to Hawk-Eye in tennis. It uses a network of high-speed cameras placed around the court to track the ball from multiple angles. The data is then processed to create a 3D model that shows the ball’s path, speed, spin rate, replacement, and more.

The system initially appeared to provide real-time match stats, all processed by its algorithm. It tracks everything throughout the match, offering players, coaches, and audiences much more insight point by point.

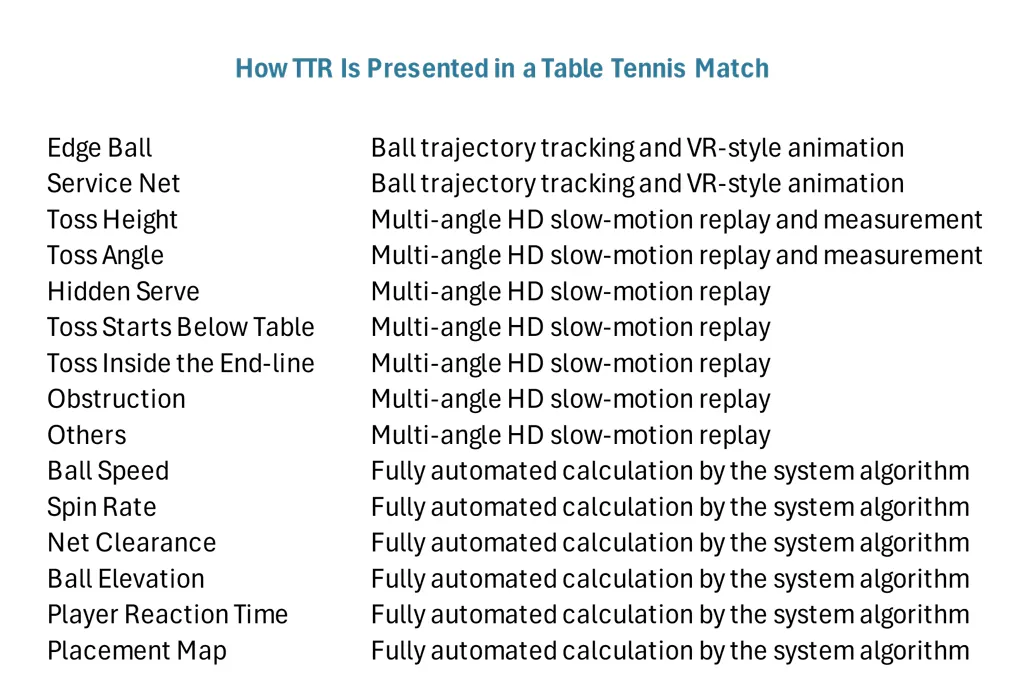

For officiating, the system presents disputed plays in different ways. Some situations are shown using 3D simulated paths or VR-style animations. Others are broken down with slow-motion replays. (I’ll go into more of the tech specifics in Section 4.)

1.1 What Can Be Reviewed and How Challenges Work

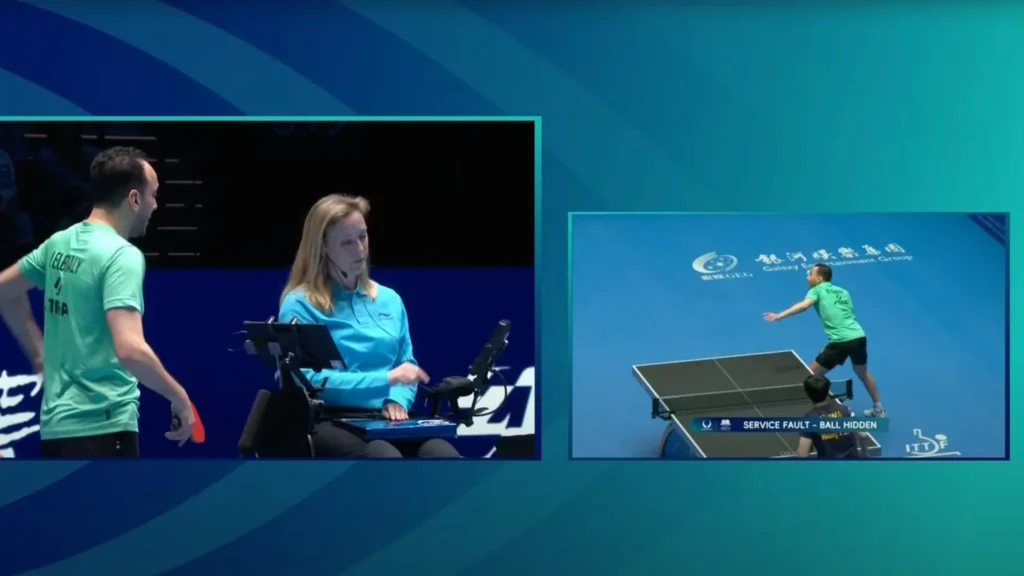

Right now, the system can review several types of situations. These include edge balls, let serves, toss height (must be at least 16 cm), toss angle (can’t go over 30 degrees), and the ball’s visibility during service. It also checks whether the toss starts below the table surface or inside the end-line of the table. In some cases, obstruction calls during rallies can also be reviewed.1

Each player is allowed two reviews per match. If a challenge is successful or if the result is unclear, the review is retained. If the call is confirmed and the challenge fails, the player loses that review. Once a challenge is raised, TTR officials evaluate the footage using the ball-tracking tools and different replay speeds before making the final decision.

What makes this special is that table tennis is the first Olympic sport to apply this tech specifically to monitor serves, not just line calls or goals. Serving has always been one of the hardest things to judge in real-time, which gives TTR a unique role.

1.2 Built on the Hawk-Eye Legacy

TTR was built on the same core concept as Hawk-Eye, which first appeared in cricket broadcasts back in 2001.2 It became a game-changer in tennis, enabling players to challenge line calls by 2006. More recently, tournaments such as the US Open in 2020 and the Australian Open in 2021 adopted fully automated line calling with Hawk-Eye Live.3

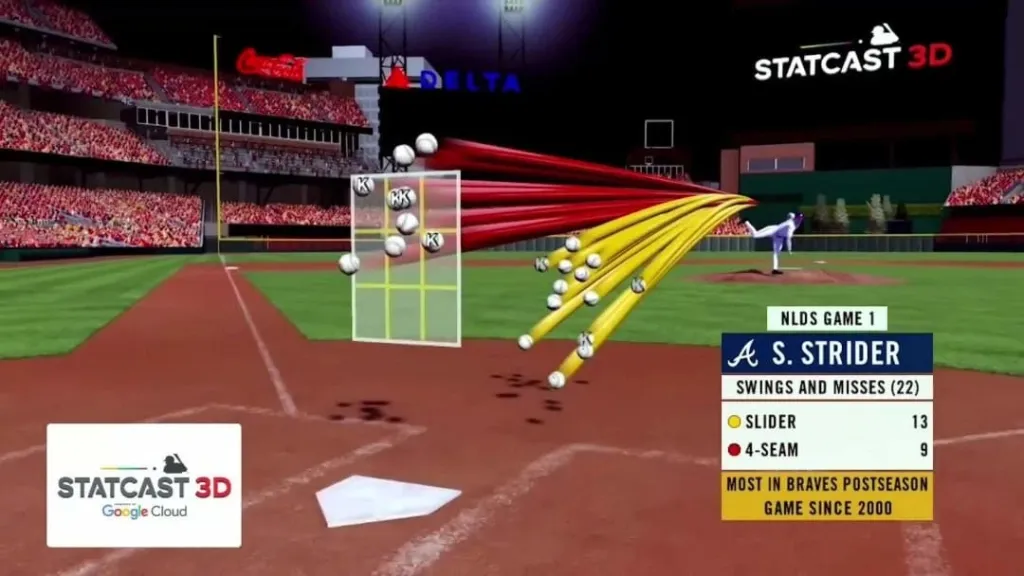

Other sports have also jumped in. The NHL has used Hawk-Eye’s SMART replay system for over a decade, now tracking players’ 29 skeleton points and 3 stick sensors.4 Soccer has relied on it for goal-line decisions since 2012, including in the Premier League and FIFA World Cups. Major League Baseball started using it for Statcast in 2020. The NBA adopted it for officiating in the 2023-24 season.5 The NFL also began using it for first-down measurements in 2025.

While not everyone agrees, Hawk-Eye has changed how sports are judged and how players and fans experience the game.

1.3 Why Table Tennis Needed Its Own Version

Table tennis differs from most sports. It stands out for its lightning-fast rallies, pinpoint precision, heavy spin, and intensity packed into a tight space. It’s less about raw power and more about reflexes, timing, and psychological battles fought in split seconds, as well as demanding decisions under extreme pressure with barely any margin for error.

Because of that, officiating becomes much more delicate, especially on serving. One bad call can shift the pace or cost a match. In sports like tennis, there’s more space and longer reaction windows. In table tennis, it’s all decided in a blink.

That’s why TTR couldn’t just copy the tennis version of Hawk-Eye. In table tennis, the serving is not just the start of a rally. It’s a weapon of control and psychological pressure. A good serve can win points outright and decide a game. So all serve-related details, including toss angle, toss height, and whether the ball was visible during the tossing, matter enough to be captured by the officiating system.

Additionally, the table’s shape makes ball tracking significantly more complex. In tennis, the ball’s position is judged relative to a flat ground line. In table tennis, the ball moves in a 3D space above, around, or even on the side of the table, and the validity of the shot depends on where exactly it lands. The system has to be much more precise, especially near the edges.

So the demands on accuracy, especially near the edges, are much higher. That adds another layer of complexity that other sports don’t face.

2. TTR Timeline and Milestones

The TTR system didn’t arrive overnight. It’s been years in the making, with each step building toward what we see today.

The earliest version of the system debuted in 2019 at the ITTF China Open and was officially unveiled later that year at the World Tour Grand Finals. During that event, five serve-related challenges were made, and four of them were challenged unsuccessfully, plus one edge ball was proved.6 According to the sources I could find, players could only challenge the umpire’s calls at the time, not directly protest their opponent’s actions.

Then, in 2021, the TTR system reappeared at China’s Preparation Tokyo Olympic Simulation Games. This was an internal tournament designed to prepare the national team for the delayed Tokyo Olympics. That event used 15 Hawk-Eye cameras (four overhead and 11 around the court). One standout moment came during the mixed doubles final when Wang Chuqin successfully challenged a serve call. The purpose of these “Simulation Games” was likely to help players adapt to the pressure and stricter officiating expected at the Olympics. However, due to the pandemic and possibly financial constraints, the system didn’t make it to Tokyo.

At the 2022 World Team Championships and 2023 World Championships, TTR was used only by Japanese broadcasters to present real-time match stats.

The TTR for officiating returned to international competition in 2024, during the Mixed Team World Cup. It was only available on the final day, but it played a role.7 That day featured six challenges, including one in which Team Korea secured a crucial point after a disputed edge ball against Team Hong Kong.

By early 2025, the TTR system was being used more consistently. In March, it was used at the qualification rounds for China’s National Games, where several close calls were reviewed.

From there, the TTR became a regular part of major events. It was fully used in the 2025 World Cup in April and the World Championships in May. In June, it was also introduced in the China Table Tennis Super League (CTTSL) during Stage 1. And now, it’s expected to appear at other top competitions coming up this year, including US Smash, Europe Smash, China Smash, and the WTT Finals.8

- 2019: First official use at World Tour Grand Finals

- 2021: Used in Chinese Olympic Simulation matches

- 2022-2023: Shown on Japanese TV for stats only.

- 2024: Returned at Mixed Team World Cup

- March 2025: Seen at China’s National Games (qualification)

- April 2025: Used in the Table Tennis World Cup

- May 2025: Used in the World Table Tennis Championships

- June 2025: Introduced in CTTSL (China Table Tennis Super League)

- Later in 2025: Expected at US Smash, Europe Smash, China Smash, WTT Finals

3. Officiating and TTR at the World Cup and World Championships

With the rollout of the TTR system at both the 2025 World Cup and the World Championships (WTTC), the data from these two tournaments offers a clear view of how the system has changed the game, on paper and in practice.

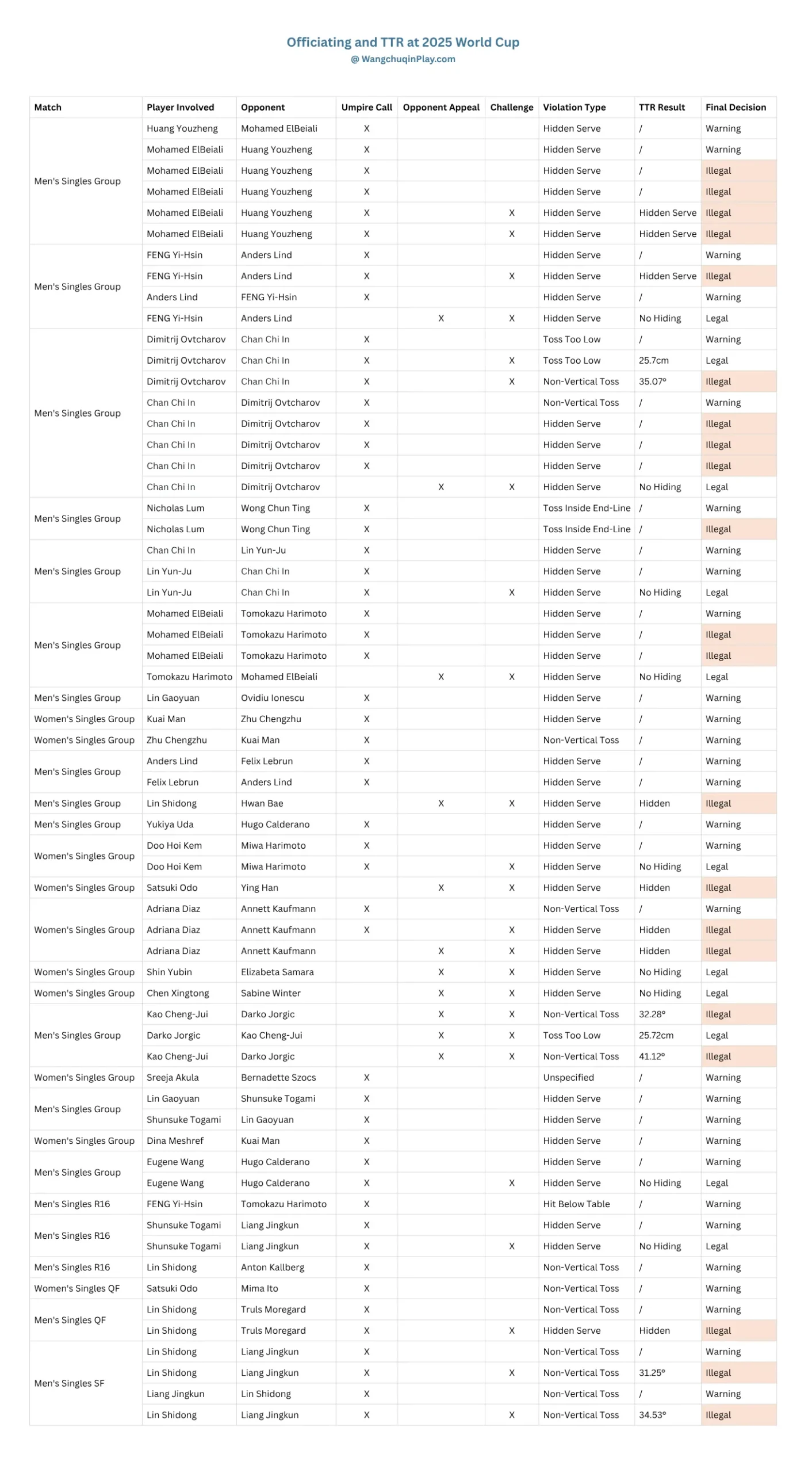

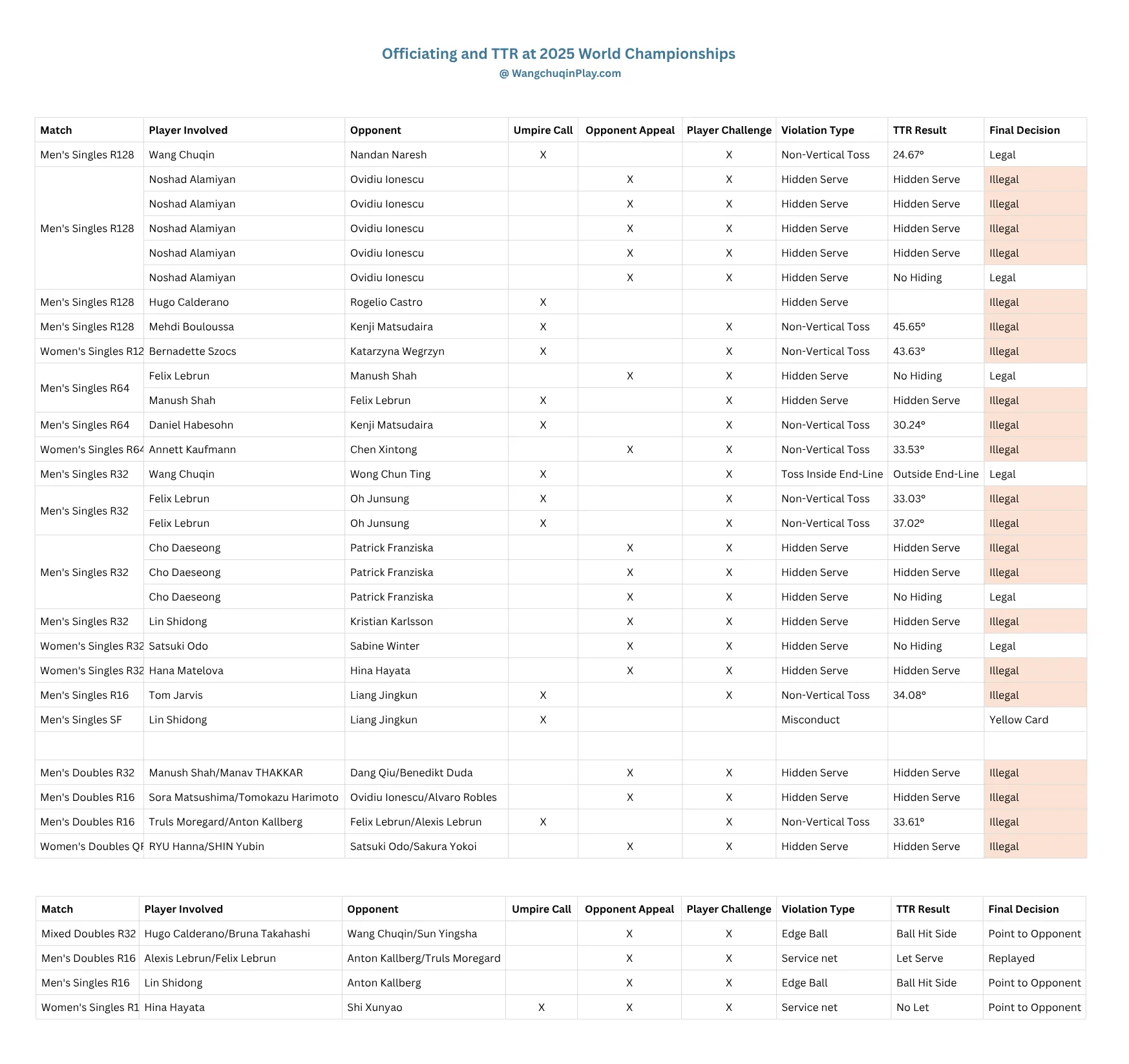

At the World Cup, umpires issued 30 warnings and called 21 service violations. Out of those 21, players challenged 13 calls. 5 were overturned, while 8 were confirmed as illegal. None of the warnings was challenged.

Separately, players also initiated 11 challenges against their opponents’ serves. After review by the TTR system, 5 were ruled illegal and 6 were ruled legal.

By the time the WTTC came around, the patterns had shifted. Umpires made just 11 serve calls in total, and 10 were challenged. Only 2 were overturned, while 9 were upheld. A yellow card was also issued for misconduct.

On the player side, 16 appeals were made against opponents’ serves. 12 were confirmed illegal, and 4 were legal. Beyond serves, the TTR system also reviewed 2 edge ball disputes, both confirmed as “hit side”, and 2 net service cases.

At WTTC, Wang Chuqin was called twice for his service. In the men’s singles R128, the umpire ruled his toss angle illegal, but TTR confirmed it was 24.67°, within the 30° limit. In the R32, he was called for tossing the ball inside the end-line, but TTR showed the toss was outside. Both challenges were successful and were the only ones that overturned umpire decisions at the tournament. Quick, clear, and confident.

These numbers point to several key takeaways:

- Umpires were more cautious at WTTC, calling fewer service faults.

- Players were more active in appealing to their opponents at WTTC, and the successful rate jumped from 45% at the World Cup to 75% at WTTC, suggesting a more selective and confident use of appeals.

- Umpire accuracy also improved, rising from 76% at the World Cup to 82% at WTTC. Still, hidden serves remain the toughest calls to get right, even with replay.

- Some players may have started using TTR tactically to slow down the game or throw off the rhythm. As German umpire Kerstin Duchatz warned, “I hope that TTR will not just be used primarily by the players as a tactical tool as I’ve experienced.”9

- Non-serve disputes, though rare, showed the system’s broader value, especially in resolving tricky bounce or edge-ball calls.

- No systemic bias was found. Across both tournaments, warnings and calls were issued regularly, regardless of players’ nationality, race, gender, language, or association. The officiating team was diverse, and decisions were consistent within matches.

Overall, both players and umpires showed increased accuracy and confidence with the help of TTR. What started as a backup check has already evolved into a central part of the officiating process. While it still has flaws and its tactical use may be debated, its core value is undeniable: it brings precision and accountability to one of the fastest-paced, hardest-to-call sports.

4. TTR in Action: My First Impressions vs. Reality

When I first saw the TTR system in use at the World Cup, I wasn’t blown away. It looked solid for checking the toss height and angle. The VR visuals clearly showed metrics, such as how high the ball went or how far it tilted. But when it came to hidden serve reviews, it felt off. Some replays were captured from odd angles that didn’t match the receiver’s view. That left me unsure how helpful the system really was.

But once I looked more closely at how it works, I began to understand why it’s structured the way it is.

4.1 Where It Works Well

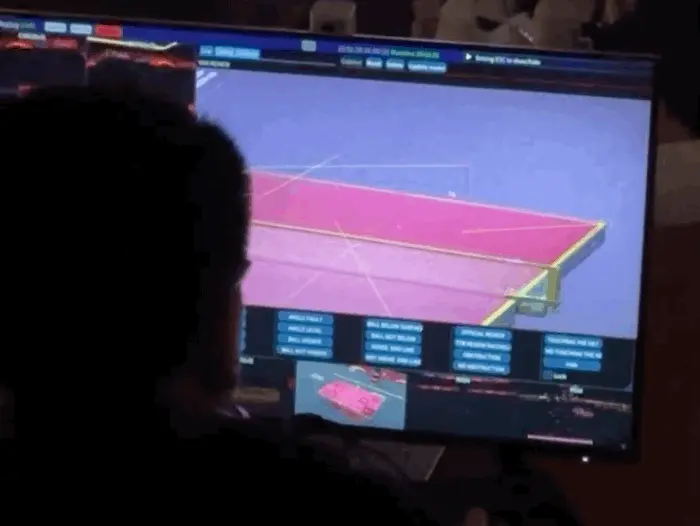

One area where the system really shines is edge-ball calls. TTR creates a 3D animation that traces the ball’s path and pinpoints the exact point of contact. That part appears to be fully handled by the system’s algorithm.

Toss height and angle reviews also work well. These use fixed-angle camera views with exact measurements. The calculations are performed manually by the tech team and then generated by the system. Once confirmed, it’s turned into a short VR animation, which can take longer than a standard replay.

4.2 Where Things Get Complicated

The toughest part is judging serve visibility, especially the idea of “visibility from the receiver’s view.” As I analyzed, even with advanced equipment, optical illusions can still fool people because of how small and fast the ball is, and how tricky the spacing between the ball and the players is.

At first, I hoped we’d get a fully accurate 3D scene showing what the receiver sees in real-time. That would require tracking not only the ball’s path and the server’s motion, but also the receiver’s exact position and eye level.

But Jayden kept reminding me how impractical that would be. Tracking unpredictable human movement is much harder than tracking a ball.

Simulating everything would mean combining motion capture, calculations, and visual modeling in just a few seconds, with the level of detail needed for a visibility call—and that’s still out of reach. That’s probably why TTR still relies on slow-motion replays from multiple angles to keep things clear and straightforward.

Then there’s the issue of perspective. According to ITTF rules, the ball must be visible to the receiver throughout the toss.10 But since receivers are free to move, the “receiver’s view” keeps changing whenever they want.

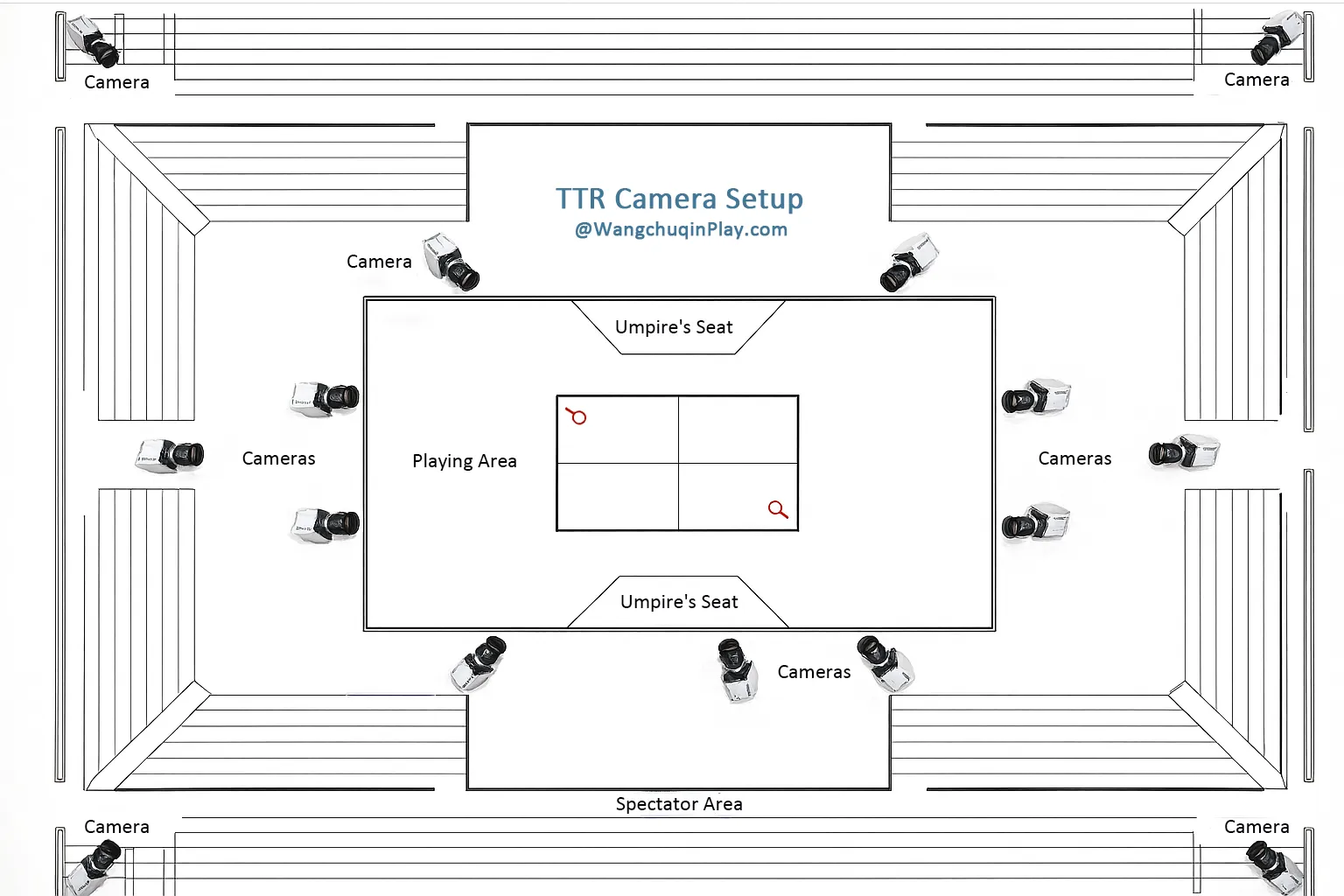

For example, right-handed players often serve from the left side of the table, which causes receivers to shift slightly to their left for a better viewing angle across the table. Left-handed servers reverse this pattern, causing receivers to move in the opposite direction. So how can the system consistently capture what the receiver actually sees? The TTR camera setup is designed to capture these typical movement patterns.

4.3 Camera Setup for Serving Visibility

First, the replay resolution is quite good, and slow-motion clips load faster than the more complex VR toss renderings.

Second, the TTR system uses fixed cameras. Based on the info I’ve gathered, each side of the table has three main ones. One in the center and two placed about a third of the way in from each sideline. These side cameras appear to be the primary source for reviewing hidden serve challenges.

In most cases, this setup works fairly well. For example, when a left-handed server stands on their right side, the right one-third camera on the receiver’s end often captures a view close to what the receiver sees. Many of the hidden-ball reviews at the World Cup and WTTC came from these angles.

But not all the replays were ideal. Sometimes the footage came from above or too far away, which seemed like an operating error. And in some situations, it didn’t quite work, such as when receivers kept moving while waiting for the serve or didn’t stand in the usual spot most players do.

This also highlights a problem with the rules. If the receiver’s position defines what counts as “visible” and the receiver can move freely in unpredictable or strategic ways, how is the server supposed to guarantee the ball stays visible? And how can a player develop a serve that’s both tactically consistent and legally safe under that kind of uncertainty? In my opinion, that part of the rule needs to be reworked.

German coach Jorg Rosskopf made a good point: “Reviewing via TTR currently takes too long, often up to two minutes. This interrupts the game and throws the players off their rhythm, causing stress for some. The camera angles could also be improved.”11 I agree. The review system still needs refinement, in both presentation and speed.

Another point is how the replays are read. Unlike toss height and angle, which are tracked with stats from the 3D model, serve visibility is still decided by the umpire’s personal judgment. As we discussed, human judgment is always an interesting part of sports, sometimes dramatic and sometimes controversial, but maybe that is also part of the appeal. However, since the racket incident at WTTC Doha, when the umpire broke Wang’s racket before he even entered the court, I have lost some trust in them. If the umpires handled the biggest table tennis tournament in such an unprofessional and biased way, I cannot say WTT’s commercial tournaments will be any better.

5. A Look Behind the TTR

Before TTR became a standard part of major tournaments, I didn’t realize how many people it takes just to support one match. Most of us focus on the players, the rallies, the scores, or the arena atmosphere. But just out of view is a full team working to keep everything fair and running smoothly, including the TTR crew.

Made in China, Built by Rigour

TTR was developed by Rigour Technology, a Chinese company founded in 2011. Rigour had already built smart systems for training, real-time data tracking, and officiating support across different sports. However, table tennis presents unique challenges, and TTR may be its most complex system yet.

The earliest version, Rigour Hawk-Eye, was created in 2018 to support the Chinese national team during closed training in Huangshi.12 It tracked shot speed, spin, and placement, then visualized the data to give coaches a clear picture of how each player was performing.

That opened the door to something bigger. Collaborating with the Chinese Table Tennis Association, Rigour began adapting the system for live officiating. But there was no guidebook. Everything had to be built from scratch: how to track the ball, what to capture, how to interpret the rules, and how to help umpires make the right call in real time.

To get it right, they brought in experts such as international umpire Zhao Hui, who helped ensure the system could respond as a trained human would.13 It had to handle decisions quickly, clearly, and with proper context, not just based on rulebook logic. Rigour also worked with China Central Television to improve the viewer experience. It took trial and error to strike the right balance between useful info and visual clarity.

From Concept to Competition

After rounds of internal testing, TTR 1.0 made its debut at the 2019 China Open in Shenzhen. It could track plays in real-time and generate 3D graphics for broadcast. Around the same time, the ITTF was actively seeking ways to improve officiating and presentation. Rigour’s system had already performed well in real matches, making it the top candidate for further development.

With input from the ITTF, the system was upgraded to detect illegal tosses, analyze hidden serves, improve edge and netball tracking, and enhance visuals for viewers.

By the time of the 2019 ITTF Grand Finals in Zhengzhou, TTR had reached version 2.0, with a finalized camera layout and a setup ready for high-stakes matches.

At that tournament, the system proved its worth. In a match between Liu Shiwen and Chen Meng, Liu challenged an edge ball. The TV replay made it appear the ball dropped below the table, but TTR showed it actually clipped the top edge. Liu’s challenge was successful. As Rigour VP Liu Xianzhang said, “The eye can be fooled, but data doesn’t lie.” That moment showed how TTR could correct even the most convincing on-screen assumptions.

In early 2020, the ITTF officially approved the system. It was originally set to appear at the Tokyo Olympics and other major events, but the pandemic delayed its full international rollout until late 2024.

Built for Table Tennis

From a technical standpoint, table tennis puts more pressure on officiating than most sports. The ball is smaller, faster, and spins more unpredictably. According to Rigour, TTR had to be fifty times more accurate than Hawk-Eye in tennis.14

The camera layout also had to be redesigned. Table tennis courts are compact, with tight spacing, limited angles, and constant lighting changes. The equipment has to stay sharp, stable, and responsive throughout every point.

And behind that precision is human effort. Unlike some sports where two people can handle the review system, TTR requires four trained operators per match. They rotate in shifts and stay fully focused. Every challenge and review passes through them.

The system doesn’t run itself. It’s people who make it work.

TTR isn’t perfect, and it won’t solve every problem overnight. But in a sport where the decisions happen in milliseconds and margins are razor-thin, it has already made a clear difference. It brings more fairness, more clarity, and more trust to the table.

As table tennis continues to grow, with more commercial attention and greater international exposure, it is encouraging to see real effort and investment going on behind the scenes. This sport has always deserved that level of care. Now it’s finally starting to get it.

References

- Enhanced Table Tennis Review System to Feature at ITTF Men’s and Women’s World Cup Macao 2025 – ITTF ↩︎

- Hawk-Eye – Wikipedia ↩︎

- Automated Line Calls Will Replace Human Judges at U.S. Open – The New York Times ↩︎

- NHL expanding use of Hawk-Eye measuring and tracking – Sportsnet.ca ↩︎

- The astonishing Hawk-Eye technology NBA is set to introduce to improve officiating and change TV game broadcast forever | The US Sun ↩︎

- Zhang, L. (2021). Analysis of the introduction of “Hawk Eye” technology on the development and impact of international table tennis competitions. Sport Leisure Mass Sport, No. 17, 2021 (in Chinese). ↩︎

- Table Tennis Review System Returns with a Successful Trial at ITTF Mixed Team World Cup 2024 – ITTF ↩︎

- 瑞盖科技携手WTT,为2025年全球顶级乒乓赛事提供TTR鹰眼回放技术服务-北京瑞盖科技股份有限公司 ↩︎

- World Cup: Duchatz’ souveräner Auftritt, Calderanos großer Triumph – tischtennis.de ↩︎

- ITTF Statutes 2025 ↩︎

- Jörg Roßkopf: „Wenn sich nichts ändert, verliert der World Cup seinen Glanz!“ – tischtennis.de ↩︎

- Chen, S. (2020). Made in China: Table Tennis Hawk-Eye Goes Global. Table Tennis World, No. 7, 2020 (in Chinese). ↩︎

- Chen, S. (2020). ↩︎

- Chen, S. (2020). ↩︎

Leave a Reply