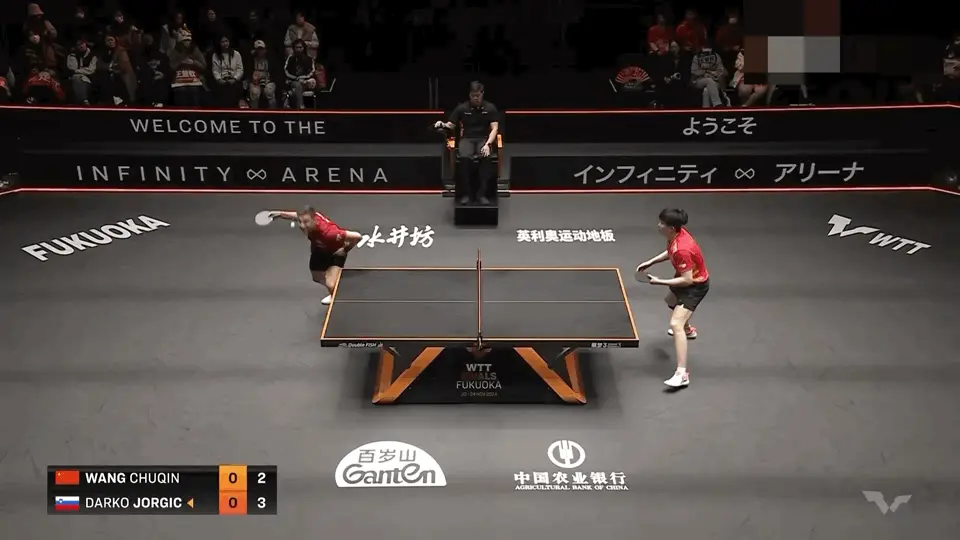

Left-handers in sports are like an accent, uncommon yet striking. In table tennis, they have natural edges but often face extra hurdles along the way. Among today’s left-handers, Wang Chuqin stands out as both the leading star and a case study in how systemic bias has long shaped their fate on China’s national team.

In history, left-handers have risen high in both singles and doubles, yet at the top stage, singles breakthroughs remain rare while doubles triumphs come often. That uneven shine hardens into a box that sidelines them, a box built within a system in China long tilted to the right hand.

Notes

1. “CNT” refers to the Chinese national table tennis team.

2. Here we focus on the men’s squad; the women’s team has different patterns and dynamics.

1. The Left-Handed Edge and Why It Fades

1.1 The Advantage of Unfamiliarity

Rarity breeds unfamiliarity, and unfamiliarity creates advantage. Left-handers make up only around 10% of the general population, yet they appear in far greater numbers across interactive sports.1 In tennis,2 in fencing, in baseball,3 the pattern is the same: left-handers’ angles, spins, and timing often throw off opponents accustomed only to right-handed play. Studies have shown that players predict right-handed movements more accurately than left-handed movements, regardless of their own handedness.4

Table tennis fits squarely into this law. Approximately 20% of today’s ITTF men’s top 20 players are left-handed, which is double their share of the population. Here are a few examples of how this difference plays out in practice:

- Spin variation: left-handers generate sidespin that runs opposite to the usual training patterns, forcing awkward adjustments and mistimed returns.

- Serving adaptation: they often tailor their serves to the opponent’s handedness, while many right-handers stick to the same patterns regardless of who stands across the table, which makes them easier to anticipate.5

- Early initiative: left-handers frequently follow serves with aggressive topspin, seizing momentum through the third-ball attack.

- Forehand cross-court: their forehand cross-court drives straight into a right-hander’s backhand, usually the weaker wing, driving them back on defense and allowing the left-hander to dictate play.

- Backhand cross-court angle:6 by contrast, their backhand cross-court naturally bends into a right-hander’s wide forehand, one of the hardest zones to cover. Although backhands are usually weaker than forehands, this angle is faster and less predictable.

Yet at the highest level, the edge steadily erodes. What once felt unpredictable is studied into routine. Rivals drill with left-handed sparring partners, analyze endless footage, and build targeted game plans.7 Rule changes have also cut into their surprise factor: a larger and later ABS plastic ball has slowed play and reduced spin, stretching rallies while demanding more speed and power. With sharper equipment and analytics that make tendencies transparent, the mystery disappears and hesitation vanishes. Performance depends more on skill and development than on natural traits.

This creates what you might call a representation-conversion paradox. Left-handers are well represented near the top but rarely turn that into titles. They account for about a fifth of the men’s world top 20 today, yet across 58 World Table Tennis Championships (WTTC), only two champions have been left-handed: Jean-Philippe Gatien in 1993 and Wang Chuqin in 2025.

That helps explain why lefty-versus-lefty finals are such a rare sight. Gatien, the most famous left-handed champion of the 20th century, shared his prime with fellow southpaw Jorg Rosskopf, yet the two almost never crossed paths deep in major singles draws. More recently, Wang Chuqin’s victory over Lin Gaoyuan in the 2022 WTT Macao Stars of China final felt like an exception rather than a norm.

1.2 Doubles: The Power of Left-Right

If singles highlight the left-hander’s unique traits, doubles magnify their structural value. Across racket sports,8 left-right pairs are favored because their court coverage and positioning are stronger than those of same-handed opponents.

In table tennis, the alternating-stroke rule forces partners to take turns on every shot, making coordination and rhythm far more important than in singles. With two forehands pointing toward the middle, a left-right pair controls the most contested zone with their strongest wings. Right-right pairs, by contrast, often hesitate or collide there. The left-hander’s presence also adds another layer of unpredictability.

- Serve and third-ball play: Left-handers swing serves into unusual zones, pulling opponents wide or toward their weaker side. With serves pre-signaled, the right-handed partner steps in straight away for a forehand third-ball attack.

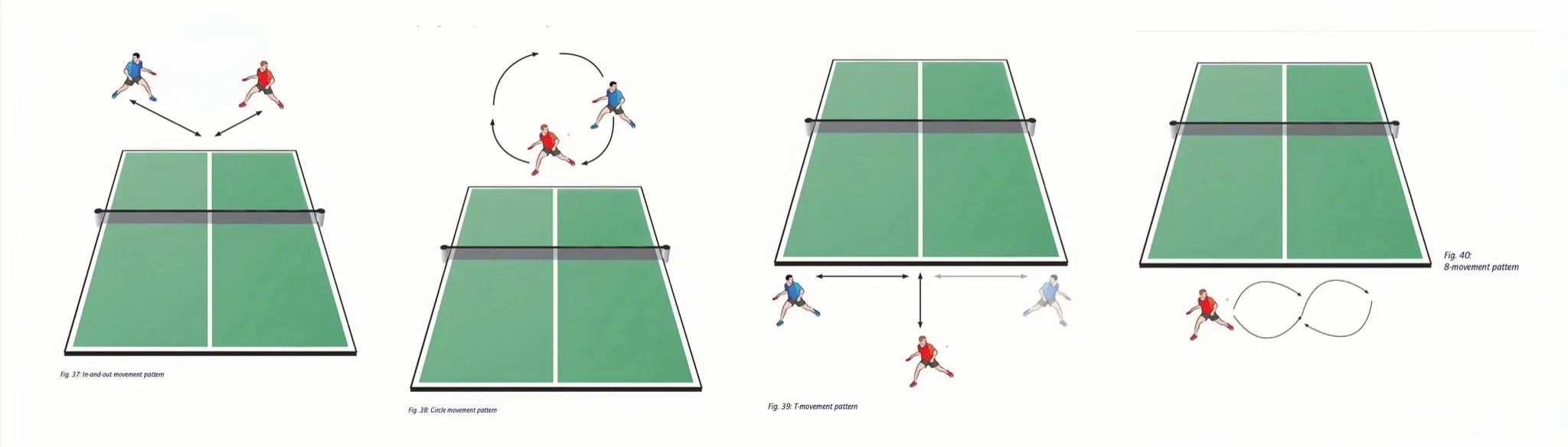

- Footwork patterns: Left-right pairs favor the in-and-out pattern, with each player stepping in for their shot, then retreating to create space. This maintains fluid movement and prevents collisions. Same-handed pairs often rely on the circle pattern, looping wide around each other, which takes more time and leaves openings. Beyond these basics, the T-pattern (for mixing distances) and Figure-8 (for recovery) are situational tools for any team, but they are easier and generally more effective with left-right pairs.

- Psychological and tactical disruption: Facing a left-right team, right-right opponents must deal with the lefty’s unusual angles and alternating strokes back-to-back within the same rally.9 That constant switching breeds hesitation, and errors soon follow.

Klaus-M Geske, Table Tennis Tactics: Be a Successful Player. (2017)

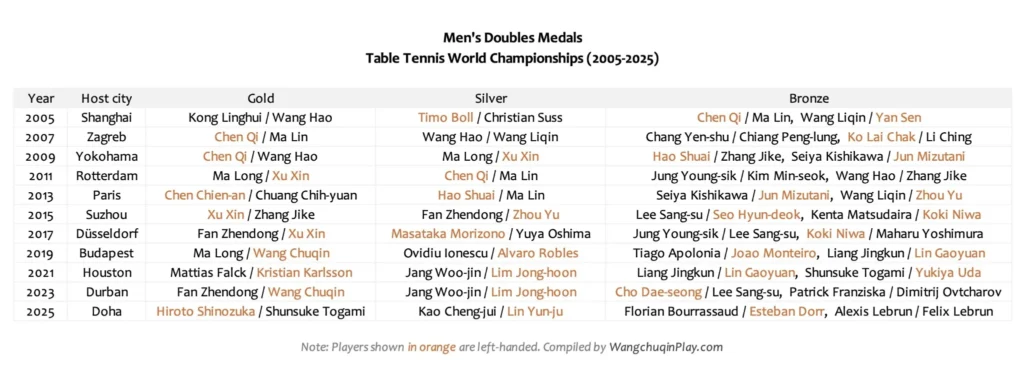

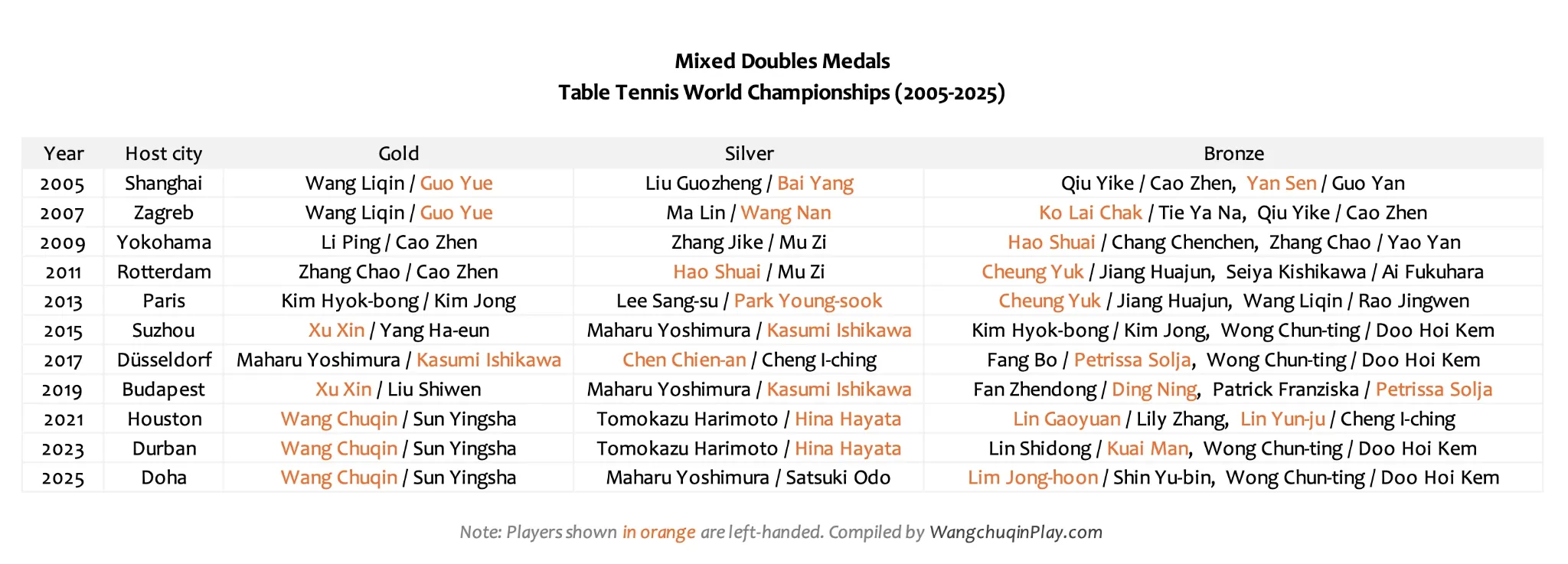

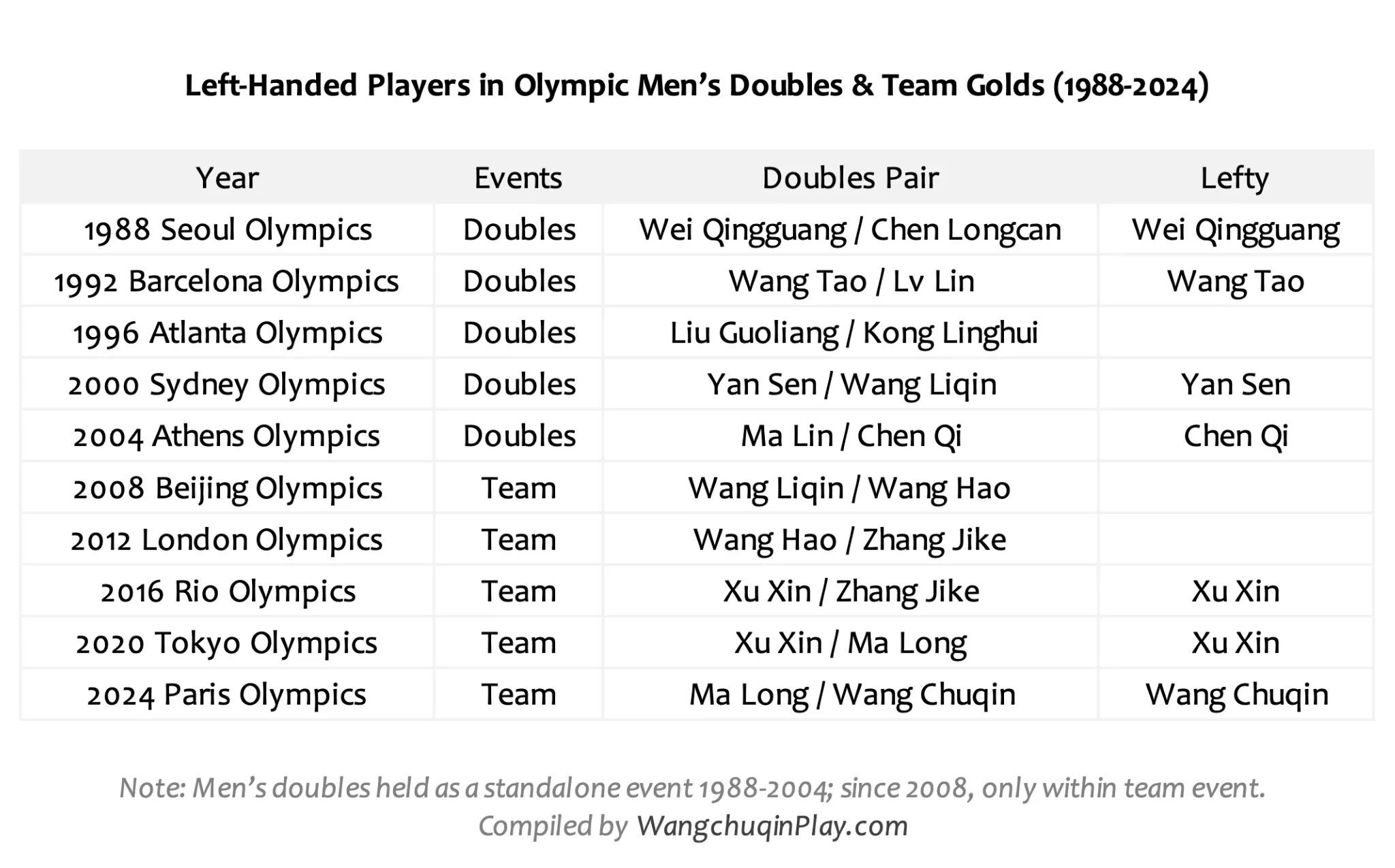

History confirms the payoff. From 2000 to 2020 at the World Championships, left-right pairs claimed 10 of 11 men’s doubles titles and 8 of 11 mixed doubles crowns. In Olympic table tennis (1988-2024), China never missed a men’s doubles or team gold medal, and 70% of them came from left-right pairs. Medals came from talent and skill, but rhythm and synergy often tipped the balance.

Over time, however, the advantage leveled out. The left-right formation that once tilted the table became the norm, and when both sides lined up that way, the structural advantages no longer decided matches. What mattered most was execution, teamwork, and rhythm. The left-hander remained essential. Without one, a pair was often handicapped, but no longer unique.

As singles traits faded and doubles balance became routine, left-handers lost their decisive edge, and within the system, they were treated less as the trump cards than as supporting tools. Chinese national team, with its deep pool of right-handers, leaned harder into a proven formula: right-handers as the singles core, left-handers as the doubles guarantee.

2. Chinese National Team: Bias Baked Into the System

At the top level, talent and effort are the baseline rather than an advantage. Every player in the Chinese national team trains to exhaustion, and every prospect has the talent to win. What creates distance is how the system directs that work.

Chinese table tennis operates within a strict hierarchy, from local and provincial squads to the national team, with authority concentrated at the top. Resources are scarce and decisive. Coaching time, training focus, sparring partners, and competition slots function like currency. Once a Chinese player is labeled as the “long-pips player,” or “defensive chopper,” their calendar bends toward team duties, as a sparring partner for core players preparing for specific opponents, and the hierarchy reinforces the role.

This is why the system matters more than raw talent or effort. It amplifies some paths while narrowing others, and those effects compound across years of training and competition. In China’s centralized sport machine, the choices hardened into two tracks: a right-handed gold standard and a doubles-first path reserved for left-handers. The bias resides less in any single choice than in the way a vast sporting power optimizes for collective medal counts over individual development.

2.1 The Right-Handed Gold Standard

For decades, right-handers defined excellence. Jan-Ove Waldner, Liu Guoliang, Ma Long, and Zhang Jike set the benchmark. Their strokes, footwork, and rally patterns became training manuals, and even coaching lineages were built around their habits. As more right-handed champions appeared, the majority template sank deeper into the system, carrying the weight of historical inertia from one generation to the next.

Historically, nearly all of China’s men’s singles world champions have been right-handed. Their success created a proven formula in coaching and talent development. When they moved into coaching or decision-making roles, their presence became structural reinforcement, passing the right-handed mold from the floor to the bench.

If two young players showed equal promise, one right-handed and one left-handed, the safer choice was almost always the right-hander. The road for them was proven and paved. For the left-hander, it was uncertain. Why bother exploring a new path?

Growing up in this environment, left-handers were told to “mirror” the right-handed gold standard rather than develop their own identity. Take their backhand cross-court again as an example. Everyone knew it was a classic lefty weapon, and right-handers studied it closely to prepare for the threat. However, within China’s system, it was rarely refined or adapted for its own left-handers.

In footwork drills, right-handers are drilled to guard the backhand corner and pivot into forehands. Left-handers flip these angles with greater efficiency, but CNT trained them as “mirror-righties,” simply reversing those drills instead of developing lefty-specific tactics. The result was technically sound footwork but strategically limiting.

Sparring also tilted right. A right-hander could find a dozen quality partners for preparation, while a left-hander often had far fewer. This flow of resources in partners, coaching attention, and event slots created compounding advantages that talent alone could never equalize.

Even in match analysis sessions, the strategy centered on right-handers. Left-handers were sidelined, forced to adapt lessons never meant for them. What separates champions from runners-up is usually the quality of preparation. Then what do you expect when left-handers must breed themselves? Not until March 2019 did CNT hold its first internal meeting dedicated to the training and career paths of left-handers.

Xu Xin’s Weibo, March 22, 2019: “Thanks to the coordination of the authorities and coaches, our table tennis team had its first-ever training session specially for left-handed players. I feel truly honored. The day I’d been waiting for has finally arrived.”

This cycle reinforced itself. Right-handers gained early access to coaches, resources, and trust. Over time, they produced more champions who returned as coaches, thereby deepening systemic bias. Talent selection perpetuated the cycle: when ability was comparable, left-handers were treated as exceptions and chosen last, while right-handers were the steadier investment.

(I need to note here: CNT’s selection process and standards for major competitions have never been clear or consistent. Decisions often came down to personal preference, which only highlighted the system’s autocracy.)

Sounds ironic? In a world that celebrates diversity, table tennis still treats left-handers as outsiders. Yes, CNT, my finger is pointed at you.

2.2 Doubles First, Singles Later

So where did left-handers fit? If the right-handed standard defined CNT’s model, the “doubles-first, singles-later for lefties” principle shaped its strategy. Efficiency logic drove the choice: why gamble on an uncertain left-handed singles project when a left-right pair almost guarantees medals?

Daily training followed that logic. Left-handers drilled through doubles-specific serve-receive routines and footwork built for alternating strokes, along with rehearsals that maximized the right-hander’s forehand. Much of their energy went into synchronizing with partners, serving in supporting roles for the collective.

Do these left-handers have, or have they ever had, singles ambition? Of course they do. Remember the paradox about top-level players? Once someone breaks into the highest ranks, how could he, whatever the hand he plays with, endure such brutal daily training without singles glory as his driving force? And let us not forget, how could a lefty fight through systemic suppression without that same ambition? Pull back the right-hander’s and our own “take-it-for-granted” ego before asking why this pattern became so deeply rooted.

2.2.1 The Doubles Mandate on the World Stage

The weight of the doubles came from the stage itself. At the World Championships, men’s and mixed doubles were fixtures for decades. At the Olympics, men’s doubles was contested from 1988 to 2004, then continued in the team format from 2008 to 2024, with a return scheduled for 2028. Mixed doubles entered in 2021. Because the current Olympic format limits each association to three players across all events, doubles became indispensable by design.

In CNT’s traditional hierarchy, the three-man Olympic lineup almost always included one designated doubles anchor, a role that nearly always fell to the left-hander. Once mixed doubles entered the Olympics, the demand grew stronger, and the left-hander was expected to carry both. In practice, the roster defaulted to one most trusted right-hander, aka singles specialist, one right-hander covering singles and men’s doubles, and one left-hander handling both men’s and mixed doubles.

Xu Xin’s career showed it clearly. His 2016 Olympic ticket was tied to men’s doubles in the team event, and in 2021, he was the core figure in both team and mixed doubles. Praised for versatility, he was still slotted as the “third core player,” essential but secondary.

This is the trap of path dependence. Once a left-hander proved valuable in doubles, the success reinforced the very role that limited them. Past victories became arguments for maintaining their support, turning achievement into a ceiling.

2.3 The Patterns in Practice

China has never lacked left-handed legends, but their biggest moments often came in doubles or team events. Since table tennis entered the Olympics, the path to gold for China’s men’s squad has followed a clear strategy: breaking through from the doubles.10

That story began in Seoul in 1988, when Wei Qingguang (Seiko Iseki, lefty) and Chen Longcan won men’s doubles gold, China’s first Olympic men’s title. After that, CNT leaned heavily on left-right pairs to secure gold: Wang Tao (lefty)/Lv Lin in 1992, Yan Sen (lefty)/Wang Liqin in 2000, and Ma Lin/Chen Qi (lefty) in 2004.

Even after doubles was dropped as a standalone Olympic format in 2008, the pattern carried into the team events. Xu Xin paired with Zhang Jike in 2016, Xu Xin with Ma Long in 2021, and Ma Long with Wang Chuqin in 2024. Out of China’s ten Olympic doubles and team golds from 1988 to 2024, seven were won or involved left-right partnerships. The World Championships exhibit a similar pattern, in which left-right partnerships dominated men’s and mixed doubles for more than two decades.

Here’s the catch. With the exception of Wang Tao in 1996 and Wang Chuqin in 2024, no Chinese left-hander was trusted with an Olympic singles slot. And it wasn’t because they lacked talent.

Take Xu Xin. One of the most gifted left-handers of his generation, he won the 2013 World Cup and multiple WTTC bronzes, yet he was consistently pushed toward doubles. In 2014, Xu admitted, “My ultimate goal is to break through in singles, not doubles. I’m a left-handed penholder, which brings a greater advantage in doubles, but when everyone only focuses on that, it’s like they’ve forgotten about my singles goal.”

Even at his peak, when he topped the world rankings, the conversation around him circled back to doubles. Qin Zhijian, his supervising coach and later head coach of the men’s team, reminded Xu Xin that winning a few championships doesn’t earn him more singles spots.”You need to do well in doubles before pursuing other goals. You play a connecting role between generations.” By the way, Qin, himself a left-hander, had also supervised Ma Long during those years.

For years, Xu Xin carried a heavier workload than most right-handed peers. He often entered three events at once. In men’s doubles, he rotated among partners such as Ma Long, Zhang Jike, and Fan Zhendong, constantly reshaping his style to suit them. At one 2019 tour stop, he won all three titles across 13 matches in just three days.

So when people joke that Chinese left-handers are “cursed,” it isn’t superstition but structural bias. The system benefited from their uniqueness in doubles while closing the door to singles glory. It boxed left-handers in, turning extra effort into heavier burdens rather than fostering growth. Not by ability, but by design.

A few years later, the pattern began to crack. Wang Chuqin, a left-hander of the next generation, broke through on the world stage. He fought to be an exception, refusing to be defined solely as the doubles hand.

3. Wang Chuqin’s Road Through the System

3.1 Early Promise, Familiar Track

Wang Chuqin rose through the youth system with a string of junior titles that marked him as a future star. Yet as he grew up in the national team, his left hand pushed him down a familiar track.

By 2017, Wang was already Xu Xin’s sparring partner, preparing the senior lefty for major competitions and the Tokyo Olympics. In 2018, he won the singles title at the Youth Olympics and began partnering regularly in mixed doubles, taking gold with Sun Yingsha at the Asian Games and the Youth Olympics.

Wang’s first breakthrough on the senior stage came at the 2019 World Championships in Budapest, just weeks before his 19th birthday. Partnering with Ma Long, who was then struggling with injury and a deep slump, surprised the field by taking men’s doubles gold. On paper, it appeared to be a veteran guiding a rookie through his first senior success. In reality, Wang’s sharp attacks and composure carried much of the weight. Even so, the victory was framed as a doubles success rather than a sign of his singles potential.

By late 2021, the picture got complicated. Ma Long was still affected by injuries and physical wear and tear. Fan Zhendong was brilliant but often slipped into sudden, unexplained slumps, lost in mental chaos that left him vulnerable. Liang Jingkun and Lin Gaoyuan, the main players in CNT, hadn’t delivered convincing results on the world stage. Looking across the bench, there’s no younger player who was both talented enough and tough enough to be shaped into a core singles player. Except Wang Chuqin.

But he happened to be a left-hander. What a disappointment for the authority, giving a lefty a full singles chance meant breaking their own bias, their own insistence. The choice left them tangled. Instead of grooming the way, CNT partially opened the door while still chaining him to doubles and mixed. With no one else to cover those fronts, Wang was left to carry the thankless role on everything.

In the CNT system, “collective interest above all” is drilled into players every single day. There is no room to refuse. When the coaches hand you your tasks, you are expected to swallow it all and answer with a loud promise: I’ll complete the task! Individual ambition? Personal feeling? Craps.

3.2 The Weight of Three Fronts

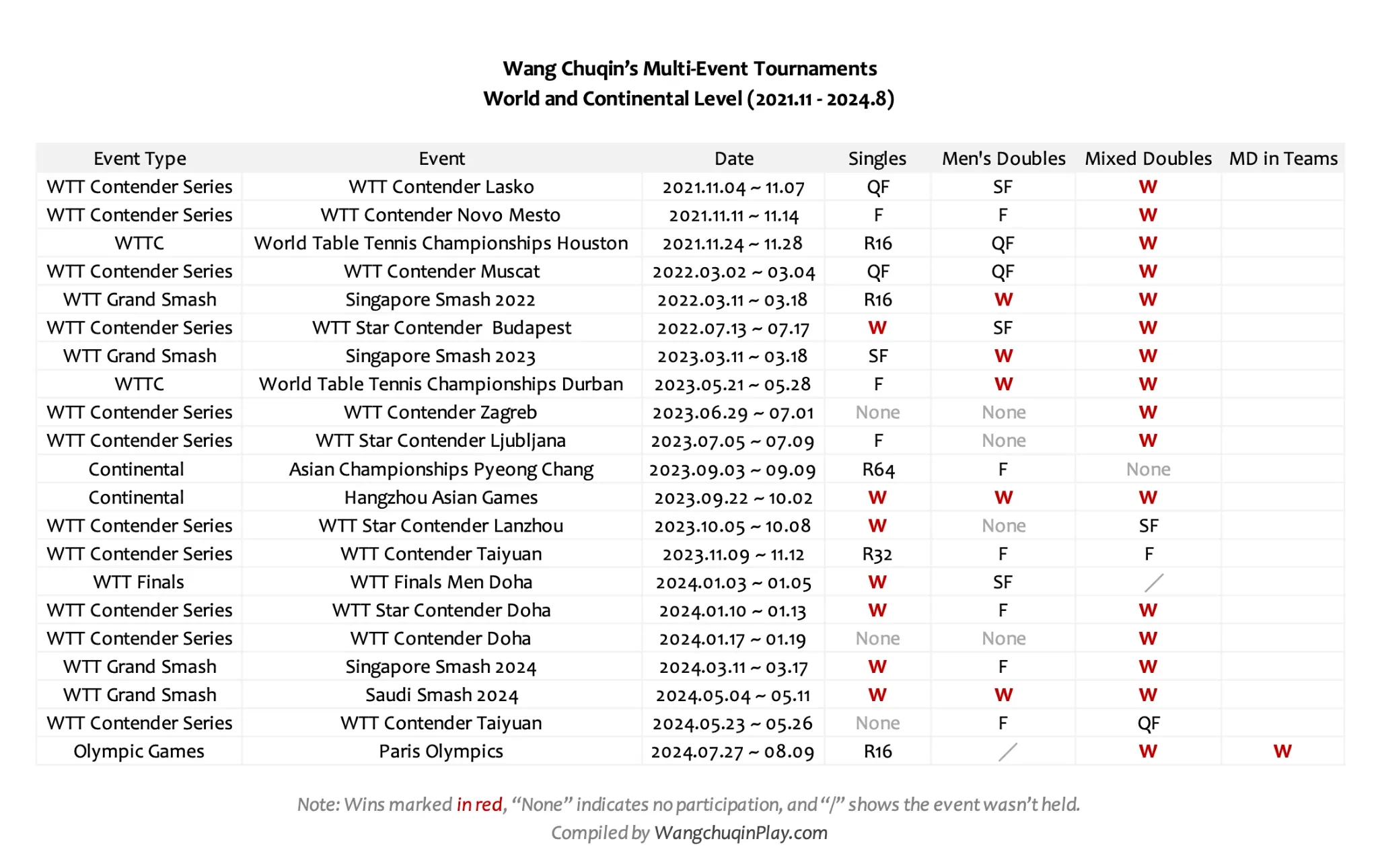

From 2021 onward, as the Paris Olympic cycle began, Wang Chuqin’s daily life turned into a survival mode. Training ran deep into the night, and at nearly every major tournament, he had to shoulder singles, men’s doubles, and mixed doubles. No one else in the squad faced such a burden.

The year-round training was punishing, but Wang never framed it that way. Rotations, multi-ball drills, endless footwork, Wang’s load outweighed anyone else’s. Ma Long once noted: “Our training was supposed to end at 10 pm, but the security guards will tell you Wang’s often still there past 11.” Fan Zhendong admitted he sometimes skipped morning sessions, while Wang almost never did and always trained the longest. Xu Xin also noted the additional challenge of being left-handed, saying he could relate. Reporters joked that he could not be interviewed, not because he refused, but because he finished practice too late. Wang himself put it simply: “Only I truly know how hard I work.”

In addition to the training came the rigors of the competition schedule. Over this cycle, Wang carried the full three-event load in 14 tournaments and competed in two events at five. Out of 21 multi-event competitions, he played only one event twice, both times in mixed doubles instead of singles, and both at lower-tier stops. It felt as if taking a break wasn’t even an option for him.

Even men’s doubles alone would have been taxing, with constant partner switches and rhythm adjustments. Mixed doubles piled on more demands. While most of the world’s top male players built schedules around singles, dipping into doubles occasionally, Wang Chuqin kept sprinting between tables, switching partners and tactics within the same day. Some days brought three or even four matches back-to-back. Where his right-handed teammates found downtime to physical and mental recovery or tactical review, Wang rehearsed doubles footwork and drilled mixed doubles serve-receive routines. Once, when asked about his condition after another three-event day, Wang shrugged and left only a few words: “I’m used to it.”

The imbalance revealed itself brutally at the 2023 World Championships in Durban. Across eight days, he logged 72 games, over ten hours on court. Wang Chuqin won mixed doubles and men’s doubles, but the exhaustion left scars. His men’s doubles opener started barely twenty minutes after finishing his mixed match. After clinching the mixed title, he had less than two hours before the singles quarterfinal. Cameras caught a drained man face-down on a training table, trying to steal a nap with his fresh gold medal beside him.

On the last day, Wang expectedly lost the singles final to Fan Zhendong 2-4. Meanwhile, Fan, the Chinese right-handed favorite, received ample breathing room and resources for years to excel in singles. Afterward, Wang admitted that by the end, he could hardly keep his eyes on the ball, and the loss in the final, in his words, “hurt me to the heart.” Apparently, that pain conveyed meaning across multiple levels.

The workhorse drained his reserves day after day, yet was still expected to deliver in singles at the end?

The same pattern played out in Doha at the 2024 WTT Star Contender. He fought through 5 matches over 11 hours, winning them all 3-0 and walking away with both the singles and mixed doubles titles. He was spotted barely able to stand on his feet post-match.

And still the load didn’t end there. Beyond the relentless training and packed calendar stood the ever-present mixed doubles mandate, a demand that reshaped his path and locked him into a cage of expectations.

3.3 The Mixed Doubles Cage

After China’s shock loss of the first Olympic mixed doubles gold to Japan in Tokyo 2021, CNT scrambled to patch the crack and elevated mixed doubles to a “never again” mission. The authorities didn’t mince words, warning the country’s most promising mixed doubles player: win the title, or risk losing your future in the sport.

In early 2023, they created the mixed doubles unit, a floating squad outside the traditional men’s and women’s teams. Coach Xiao Zhan was appointed head of that unit and placed in charge of Wang’s training. With that title came a ruthless shift in priorities. In Xiao’s own words: “If he doesn’t deliver in mixed doubles, I’ll drop him. Winning Olympic gold in mixed doubles is my one and only mission.” It wasn’t guidance but an ultimatum.

Why does the CNT always fall back on threatening its players over and over?

That unit became Wang’s cage. Up to 90% of his training was devoted to mixed doubles, leaving little room for singles. And because Xiao’s role was tied to the unit, Wang effectively lost what his peers took for granted: a steady supervising coach dedicated to his singles development. Coach Xiao was steady at Wang/Sun’s mixed doubles, but at singles-only events, his presence was uncertain or absent altogether. While teammates entered singles matches with their trusted anchors in the corner, Wang often had to make do with another player’s coach or even Wang Hao, the men’s team head who oversaw everyone but belonged to no one. Wang was a triple-event player with no clear corner to stand in.

(See my other post for Wang’s coaching situation.)

(Note: Long-term participation in mixed doubles is commonly considered to have a negative impact on the male player. Check my research: The Weight Behind the Glory: Wang’s Mixed Doubles Life)

At the 2023 Hangzhou Asian Games, over 11 days of competition, including 3 days with three matches each and 1 day with four matches, Wang made history as the first male player to win all four titles at this stage. Without a night’s rest, he went straight into the WTT Star Contender in Lanzhou, where he suffered from altitude sickness yet was still required to carry singles and mixed doubles.

After Paris 2024, he exited early in singles, sparking criticism at home despite winning two golds in men’s team and mixed doubles. Wei Qingguang, a left-handed Olympic men’s doubles champion who later coached Japan and Chinese Taipei, put it bluntly: “Wang Chuqin may have spent too much energy early on playing mixed doubles and left less in reserve for singles. This might be the fate of left-handers.”

Somehow, it felt like empathy and a verdict at once.

3.4 Turning Burden into Opportunity

And yet Wang’s story didn’t stop at fate. What set him apart was not only his talent but also the relentlessness with which he wrestled opportunity from bias and unfairness. Where the system sought to impose a ceiling on him, he turned that ceiling into the floor he built.

At first, doubles looked like a consolation prize. For most left-handers, it stayed that way. Wang made it his ladder. “Over the years, I had competed in all three events, never neglecting any of them,” he reflected. “But mixed doubles was my first step onto the Olympic stage. Winning there gave me more opportunities and helped me grow in singles and team events later.” He worked several times harder than other left-handers, and harder still than right-handed teammates who enjoy privileges. He treated the endless grind of mixed and men’s doubles as extra reps under pressure, a place to sharpen serve variation, touch, and match awareness, and then carried those gains into singles on his own terms.

“I’m playing three events… I need a training load much heavier than the matches themselves. That’s the only way I can really handle competition and not feel powerless on court. I can’t let myself feel that way, so I push to squeeze out all my potential and all my strength every day.”

That effort built a loop he controlled. The doubles victories were never his destination, but the leverage. Each win dragged him into more tournaments, more competition slots, and greater exposure. Because he refused to waste any of it, his singles career progressed steadily until it stood alongside his doubles at an unprecedented level. By then, the system’s bias could no longer contain him.

Results forced the system’s hand. Once all three events reached that standard, the CNT could not afford to sideline him. More opportunities followed, not out of fairness but because medals depended on him. Even without a steady supervising coach or the right to manage his schedule, Wang had made himself indispensable. He didn’t inherit opportunity. He forged it from the very burden meant to hold him back.

This is also where Wang stands apart from other left-handers. They fought the same system, but timing and structure kept them boxed in. By Wang’s era, CNT needed a new singles anchor, and he turned the doubles grind into preparation, sharpening skills under pressure and carrying them into singles. That rare twist of turning imposed work into leverage demonstrated how exceptional his rise truly was.

3.5 Rising Anyway

Piece by piece, Wang Chuqin built himself from scraps. Without the steady support, he had to navigate the larger men’s team on his own. From borrowing insights from any coach with a spare moment, soaking up tips from teammates, to sparring with friends, and even picking up English from staff to widen his net.

From 2021 through 2024, he did more than survive the triple load. He thrived in it. In mixed doubles with Sun Yingsha, he became World No. 1 in 2021 and stayed there for years, piling up titles at a pace no other pair matched. In men’s doubles, he rotated through different right-handed partners, cracked the world’s top five in 2022, and reached No. 1 in 2023.

Somehow, through it all, his singles career kept climbing. Wang rose to No. 3 in November 2022, No. 2 in April 2023, and finally No. 1 in March 2024. What makes his rise extraordinary isn’t only the titles but also the context. He reached World No. 1 in men’s singles, doubles, and mixed doubles at the same time, after years with scattered prep, exhaustion, and the triple duties no right-handed peer had ever matched.

By the time the World Championships in Doha arrived in May 2025, the situation had shifted. For once, Wang entered only singles and mixed, not men’s doubles. The reason was plain: with no one else in the squad ready to chase the singles title, he was China’s best chance, and the authority had to reserve his energy for it.

Yet even then, on the eve of the tournament, Wang was pulled into men’s doubles training as a sparring partner for Liang Jingkun and Huang Youzheng. His doubles experience was valuable, so he gave it, but it was no light favor. Doubles drills drain energy differently, and plenty of others could have filled the role. Now try to name a big event where teammates returned the favor for his singles while they still had matches left. Hard to find. It was something he continued to absorb on his own.

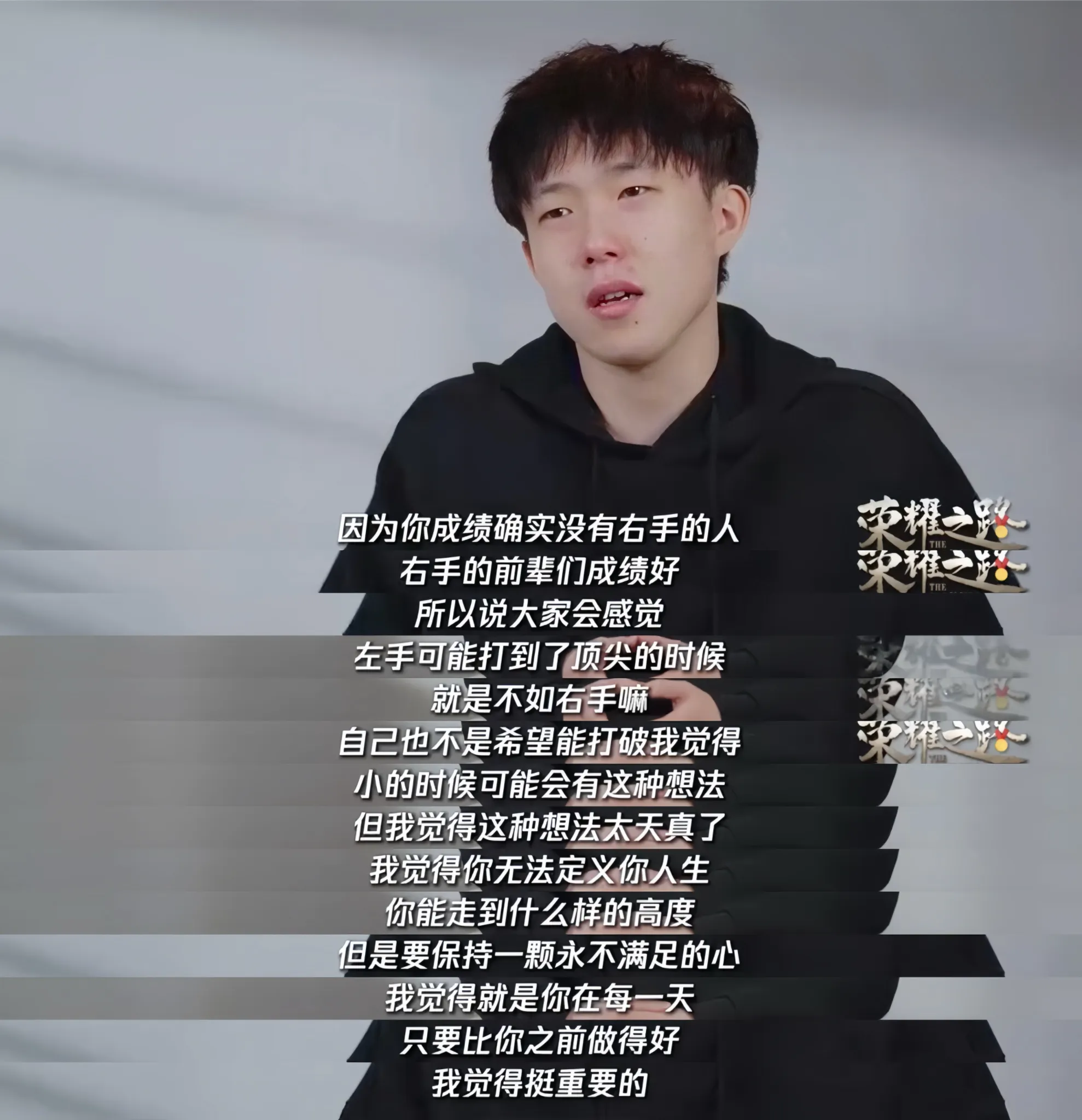

And then came the breakthrough. In Doha, Wang Chuqin made history as the first Chinese male left-hander to win a World Championships singles crown. 👑 Afterwards, he admitted, “Right now, after winning the singles title, I can honestly say I’m much happier than I was with the doubles win. I had dreamed of this moment for a long time, and now that dream has come true.” It seemed to be his first time speaking about his singles ambition.

When he lifted the singles trophy in Doha, it was more than a personal career high. It was a left-hander’s vindication, proof that bias could be bent and burdens could be turned into opportunity. But why should he have had to prove it at all?

A left-hander can fight through, as Wang did, but triumph doesn’t erase the system’s weight, the years of neglect, the drained health, and the emotional strain of carrying burdens his right-handed peers never had to bear.

4. The Left Hand’s Fate

Left-handers rise higher in sport than their numbers suggest, yet at the summit of table tennis, they almost vanish. It isn’t only that rivals adapt to their spins and angles. The deeper reason is structural. The training system has been written for right-handers, and left-handers have been shaped into doubles-first roles. Coaching, tactics, and resources have never been shared evenly. The result is a framework: the left hand pushed aside in the right hand’s playbook, then summoned back as the perfect partner.

Wang Chuqin broke out of that box, but the way he did it laid bare the cost. The compromise. The system didn’t clear the way for him. He fought through it, carrying heavier schedules, fewer resources, and the constant demand that doubles and mixed doubles had to be “done” first. That is the real curse of Chinese left-handers.

By defending China’s team glory at WTTC Doha, it briefly seemed as though something within the system might have begun to shift, but whether that change is real remains uncertain. (My view maybe more pessimistic than most.) The machinery of Chinese table tennis is vast and rigid, built to endure far longer than any single career, and it doesn’t bend easily. Even at the top, he still lacked what many right-handers take for granted, from a steady supervising coach to real control over rest and scheduling. Beyond CNT, the ITTF’s own authoritarian tendencies cast another shadow that may shape how far true change can go.

Look closer into Wang’s career inside CNT, and the surface polish starts to peel away. Beneath the medals and routine talk of collective pride runs a current of bias, unpleasant and stubborn, baked into the system. Compare his treatment with his teammates, and you won’t find balance, only more stories that tilt the same way. Small asks, one after another, piling up in the same direction. A pattern you can feel in your bones.

Wang cracked a barrier that had stood for decades. But breaking rules invites resistance. His story is both a torch and a warning. A torch that lit the way for the left hand to take center stage. A warning that, without a change in the system itself, the next generation will be forced to face the same fate.

If the sport truly values its own diversity, it must let the left hand write its own script. Not as a mirror. Not as a partner. But as a protagonist.

Sept 18, 2025: I decided to pause here for now, though it will probably never feel completely “done,” and some questions still hang in the air:

- The competitive relationships between left-handers in CNT

- How long-term mixed doubles participation affects male players

- CNT’s selection process and standards for major competitions

- And more

Read More

Mystery of China’s Coaching System Neglect – Part 2: Wang’s Career with Coaches

Wang Chuqin Part | Documentary “Blossom in Paris” | Eng Sub – YouTube

2025 WTTC Doha: Calm After the Climb 👑

Wang Chuqin: The Road to Growth | “Face to Face” Interview

Wang Chuqin’s Olympic Injury Story that We All Missed

“Giving my all to be my best self.” Wang Chuqin Shares Struggles Behind Olympic Gold & 2024 Setbacks

References

- Loffing et al. Left-Handedness in Professional and Amateur Tennis. PLoS ONE, 7(11). ↩︎

- Tennis players struggle with lefty serves that kick wide into the ad court. See: Loffing et al. The Serve in Professional Men’s Tennis: Effects of Players’ Handedness. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 2009, 9(2): 255-274. ↩︎

- In baseball, left-handed pitchers throw opposite-breaking balls while left-handed batters are closer to first base and pull more into shorter right-field fences. See: Handedness Comparison in Baseball | Sports Analytics Group at Berkeley ↩︎

- Hagemann, N. The advantage of being left-handed in interactive sports. Atten Percept Psychophys, 2009 Oct;71(7):1641-8. ↩︎

- Lanzoni et al. Do left-handed players have a strategic advantage in table tennis? International Journal of Racket Sports Science, 2019, Issue 1. ↩︎

- Gu, N. The Contrastive Study of Techniques and Tactics That Lin Gaoyuan and Wang Chuqin Against Different Players of Left or Right Hand. Master’s thesis, Beijing Sport University, 2019. (in Chinese) ↩︎

- Schorer, J. Human handedness in interactive situations: Negative perceptual frequency effects can be reversed. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2012, 30(1), 1-10. ↩︎

- Tennis teams like the Bryan brothers, and even top pickleball duos, have long chosen this setup that unsettles right-right opponents. ↩︎

- Huey, T. Study on the Competitive Advantage of Pairing Athletes with Left and Right-handed during the “Three Small Ball” Games. Master’s thesis, Chongqing Normal University, 2017, p. 3. (in Chinese) ↩︎

- 国乒双打荣耀从传承中走来_国家体育总局 ↩︎

Leave a Reply